The “Intellexa Leaks”, a new investigation published jointly by Inside Story, Haaretz and WAV Research Collective, presents troubling revelations about the surveillance company Intellexa and its signature product Predator, a form of highly invasive spyware that has been linked to human rights abuses in multiple countries.

Intellexa is one of the most notorious of the so-called “mercenary spyware companies”, a description used by civil society and industry researchers for private entities that develop spyware and sell it for use by governments. While numerous reports on Intellexa, including by Amnesty International, have documented human rights harms related to the use of its products, its internal operations have remained largely unknown to researchers. Amnesty International has previously sent detailed questions to Intellexa about its products, operations and corporate structure. Intellexa has always declined to answer these questions. In 2023, Intellexa was fined by the Greek Data Protection Authority for failing to comply with its investigations into the company.

Now, drawing on leaked internal company documents, sales and marketing material, as well as training videos, the “Intellexa Leaks” investigation gives a never-before-seen glimpse of the internal operations of a mercenary spyware company focused on exploiting vulnerabilities in mobile devices, which enable targeted surveillance attacks on human rights defenders, journalists and members of civil society.

Among the most startling findings is evidence that, at the time of the leaked training videos, Intellexa retained the capability to remotely access Predator customer systems, even those physically located on the premises of its governmental customers. Therefore, Intellexa would have access to data on those subject to targeted surveillance attacks by governments. The leaked files, covering much of the company’s recent history, include further technical evidence which forensically confirms that Intellexa’s flagship Predator spyware was used in specific cases of surveillance abuses previously found in Greece and Egypt.

Amnesty International was the technical partner on the “Intellexa Leaks”, supporting media partners with verification and analysis of the leaked data. This article outlines the evidence that Amnesty International’s Security Lab (our in-house specialists on digital security and forensics) analysed, and what we believe it tells us about Intellexa’s operations.

Predator spyware poses an ongoing threat to civil society in 2025

This new investigation by Amnesty International’s Security Lab comes at a critical time for civil society to stop human rights abuses powered by the spyware industry. The new research indicates that Intellexa’s Predator spyware continues to be used to unlawfully surveil activists, journalists and human rights defenders around the world, despite repeated public exposure, criminal investigations, and financial sanctions directed at the company and its senior executives.

Ongoing forensic investigations from Amnesty International’s Security Lab – independent of this publication – have found new evidence that Predator spyware is being actively used in Pakistan. In summer 2025, a human rights lawyer from Pakistan’s Balochistan province received a malicious link over WhatsApp from an unknown number. Amnesty International’s Security Lab attributes the link to a Predator attack attempt based on the technical behaviour of the infection server, and on specific characteristics of the one-time infection link which were consistent with previously observed Predator 1-click links. This is the first reported evidence of Predator spyware being used in the country. The targeting comes at a time of severe limits and restrictions placed on the rights of human rights activists in Balochistan province, including increasingly common province-wide internet shutdowns.

Amnesty International is continuing to investigate this and other attacks, and will release further details, as well as additional cases of Predator abuses found in Africa, in a series of upcoming reports.

These new forensically confirmed cases highlight the continued digital threat that Intellexa’s Predator spyware poses to activists and human rights defenders.

Methodology

Inside Story, Haaretz and WAV Research Collective have collaborated on a months-long investigation, the “Intellexa Leaks”, drawing on a set of highly sensitive documents and other materials leaked from the company, including internal company documents, sales and marketing material, as well as training videos. Amnesty International researchers reviewed a selection of the leaked Intellexa material as part of this collaboration to verify technical evidence and for fact-checking purposes.

The material was highly consistent with Amnesty International’s knowledge and understanding of the Predator spyware system, including non-public technical evidence gathered by Amnesty International through forensic research and other investigative efforts. Amnesty International has previously documented Intellexa’s technical capabilities, and numerous cases of abuse linked to the spyware product, as part of the 2023 Predator Files project. On this basis, our technologists were able to confirm with a high degree of confidence that the files are genuine and provide a unique perspective into Intellexa’s operations.

Significantly, the leaked material also validates independent research published by other civil society and industry researchers, including Citizen Lab, Recorded Future and Google’s Threat Analysis Group, who have tracked Predator spyware activity in recent years. In addition to verifying the authenticity of the material, Amnesty’s Security Lab analysed the leaked materials for insights into the technical capabilities of Intellexa’s spyware, and what this might tell us about the evolving nature of mobile spyware threats more broadly. The analysis, summarized in this technical briefing, was also shared with media partners to support their research. Unedited screenshots and reproductions of the leaked material are presented in the present briefing.

Cybersecurity researchers at Google’s Threat Analysis Group and Recorded Future have today published two independent, but complementary, technical briefings which provide further insights on Intellexa’s corporate structure, active customers, exploits and technical capabilities. These reports draw on separate investigations and visibility into Intellexa activities. Google has also announced a round of spyware threat notifications sent to individuals Google identified as likely Predator spyware targets, including “several hundred accounts across various countries, including Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Angola, Egypt, Uzbekistan, Saudi Arabia and Tajikistan”

Acting on behalf of the organisations working on the “Intellexa Leaks”, Haaretz wrote to Intellexa on 26 November 2025 to outline the findings from the investigation, including those in this article, and invited them to comment. On 3 December, a legal representative acting on behalf of Tal Dilian, the founder of Intellexa, sent a written response to Haaretz that states that he has “not committed any crime nor operated any cyber system in Greece or anywhere else”. The full statement does not provide specific answers to the questions posed or allegations raised by the evidential findings in the Intellexa Leaks. The verbatim response letter can be viewed in full in the articles by Haaretz and by Inside Story.

Key finding 1: New insights into Predator infection vectors, including attacks via advertising ecosystems

The leak provides fresh insights into the broad capabilities, system architecture and infection vectors used in Intellexa’s spyware product.

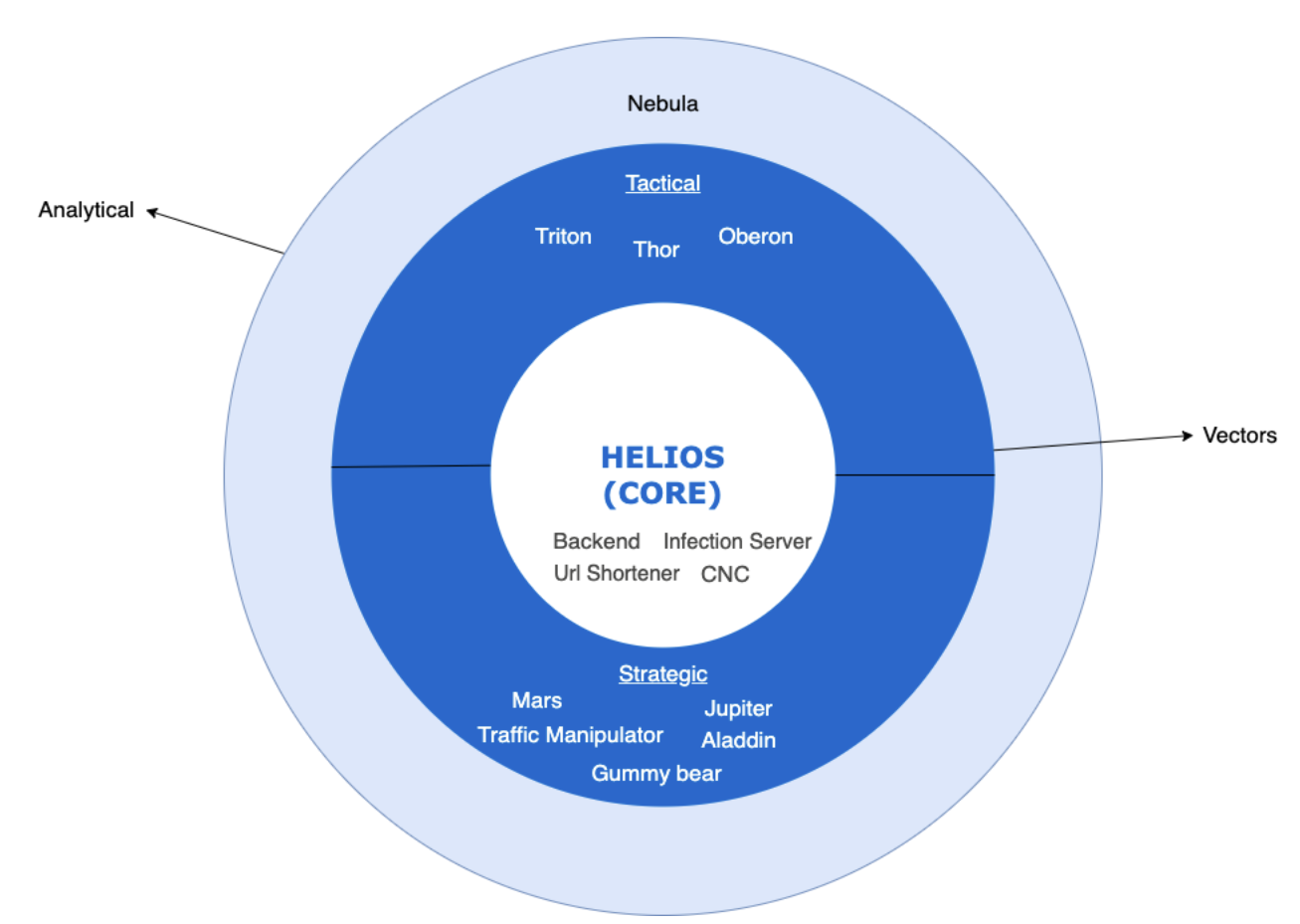

Intellexa has rebranded their flagship mobile spyware product on multiple occasions: best-known externally as Predator, the broad system has also been marketed as Helios, Nova, Green Arrow and Red Arrow. In this technical briefing, the system will simply be referred to as Predator for ease of reference. While the product appears to have evolved over time, the broad architecture and focus on remotely infecting mobile devices has remained the same.

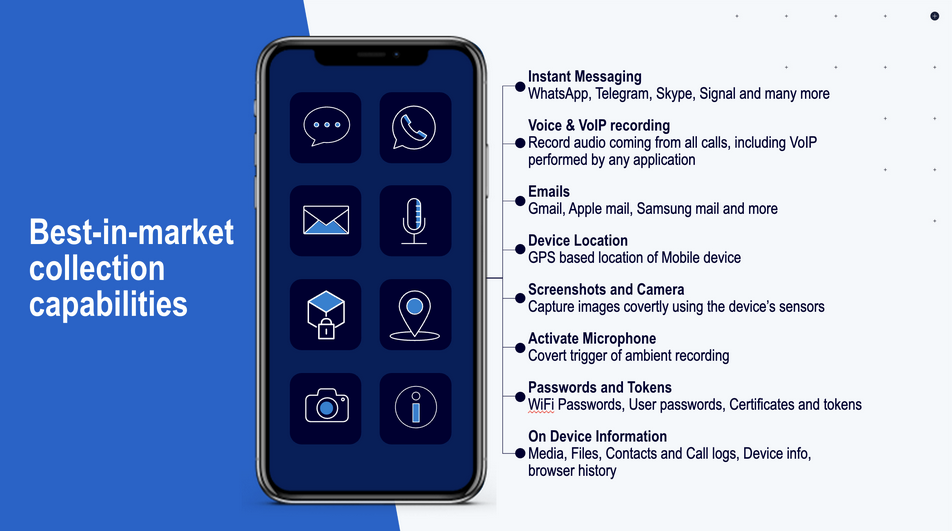

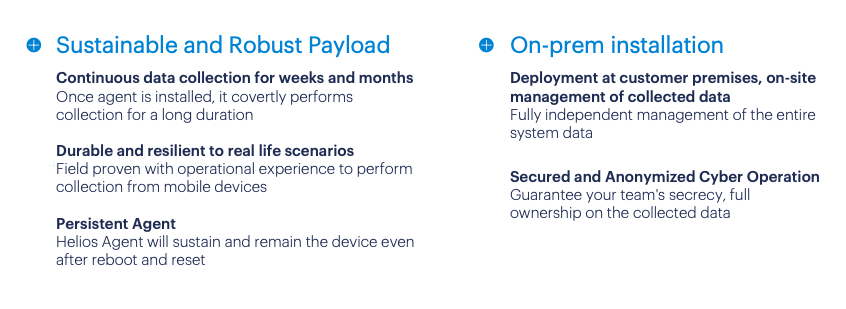

Unlike spyware made by competitors, Intellexa’s Predator relies, almost exclusively, on so-called “1-click” attacks to infect a device, which require a malicious link to be opened in the target’s phone. The malicious link then loads a browser exploit for Chrome (on Android) or Safari (on iOS) to gain initial access to the device and download the full spyware payload. Company marketing material (see Figure 1) shows the extensive data available once the spyware is installed, including ability to access encrypted instant messaging apps like Signal and WhatsApp, audio recordings, emails, device locations, screenshots and camera photos, stored passwords, contacts and call logs, and also to activate the device’s microphone.

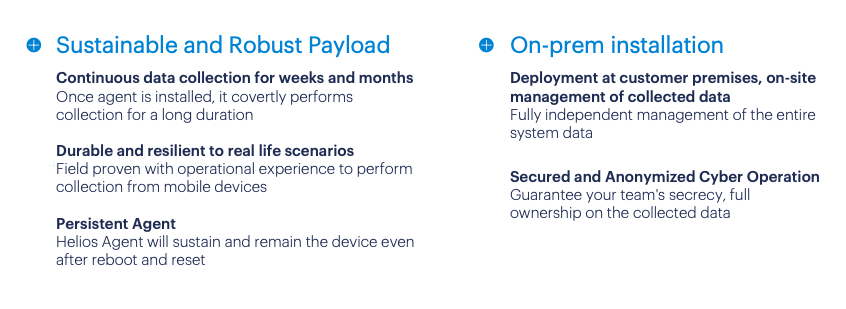

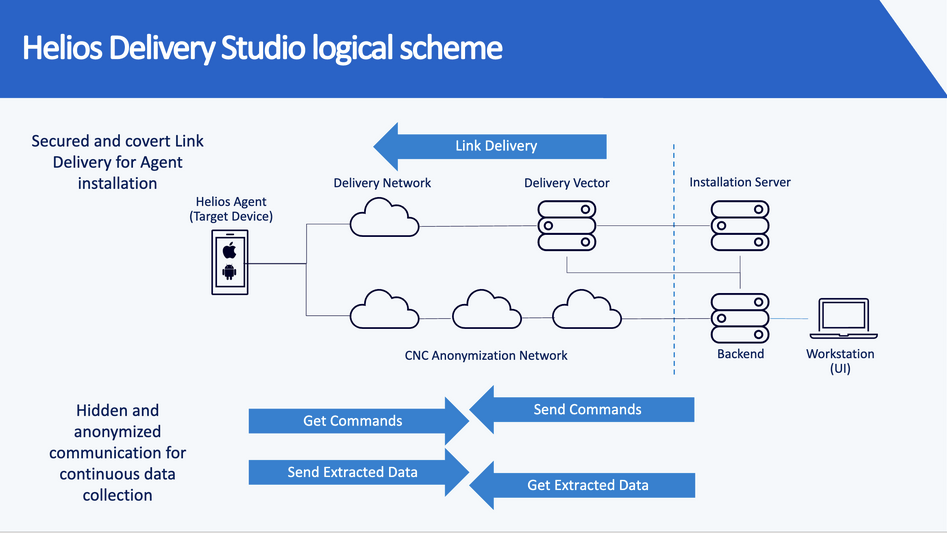

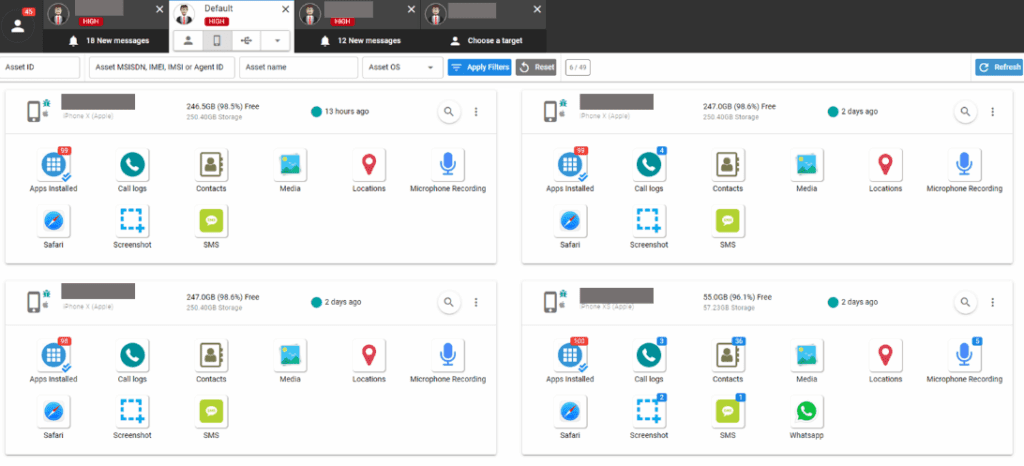

After successful installation on the target’s device, the spyware ultimately communicates with, and uploads surveillance data to a Predator backend server physically located in the customer country (Figure 2). In an attempt to hide the ultimate identity of the spyware operator, all data from the spyware is first relayed (Figure 3) through a chain of anonymization servers, termed the “CNC Anonymization Network”.

The reliance on browser exploits means that the spyware operator must successfully trick the victim, or otherwise cause them to open the malicious link. If the link is not opened, the infection will not proceed.

Each time a 1-click attack link is sent to a target, it also creates a risk of exposure for the operator. A suspicious target may share the attack link with digital forensic experts, which could reveal the attack attempt and operator.

‘Tactical’ and ‘Strategic’ infection vectors

To overcome this limitation, Intellexa has designed several ‘delivery vectors’ (Figure 4) which are different approaches to triggering the opening of an infection link on the target’s phone, without needing the target to manually click the link. This allows Intellexa to offer zero-click like functionality, without needing additional zero-click exploits.

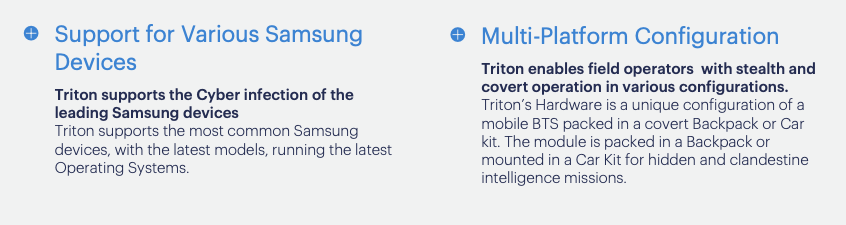

Triton, Thor and Oberon are so-called ‘Tactical’ vectors. Tactical is a term used in the cyber-intelligence industry to describe attacks which require physical proximity to the target, either physical access or being within WiFi or radio range.

Amnesty International’s Security Lab has previously identified Triton as a Samsung baseband exploit. A baseband exploit targets the low-level phone software and hardware responsible for radio communication with the mobile network. The leak confirms that the exploit targeted Samsung Exynos devices (Figure 5), although it is unclear if the attack vector has been active in recent years. At this stage, we have not yet identified Thor and Oberon, but they are likely similar to other local attacks, either targeting phone radio communications or perhaps relying on physical access to a device.

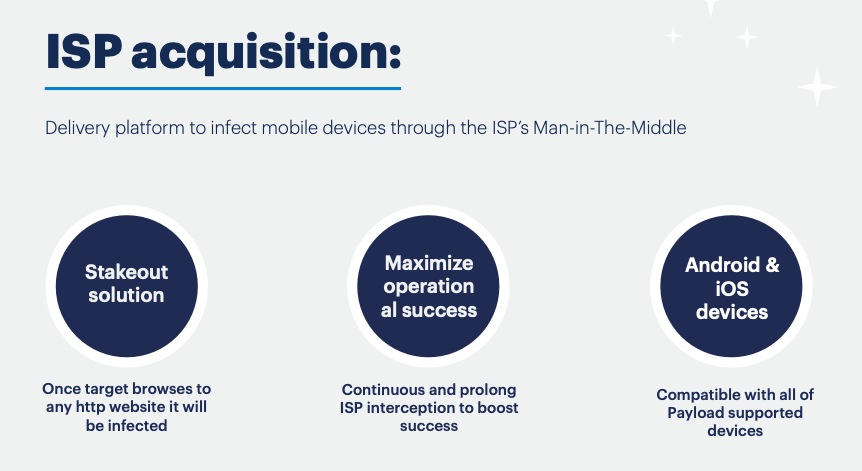

The ‘Strategic’ vectors are delivered remotely via the internet or mobile network, and include ‘Mars’, ‘Jupiter’, and ‘Aladdin’. The ‘Mars’ and ‘Jupiter’ vectors are network injection systems which require cooperation between the Predator customer and the mobile operator or the target’s internet service provider (ISP), as shown in Figure 6. ‘Jupiter’ appears to be an extension of ‘Mars’, enabling successful network injection on domestic HTTPS websites, for which the customer has valid TLS certificates.

Fundamentally, these systems enable the attacker to silently inject a Predator infection link into the target’s browser while they browse the web. Described as a ‘stakeout solution’, the attackers can activate the infection, and then simply wait for the target to open an unencrypted HTTP website, or browse to a domestic HTTPS website, which was intercepted with Jupiter.

However, these types of network injection attacks have become increasingly difficult to carry out with the shift to HTTPS-only web browsing.

‘Aladdin’: Silent Predator infection by exploiting the mobile advertising ecosystem

Intellexa has developed a new strategic infection vector, ‘Aladdin’, which could enable silent zero-click infection of target devices anywhere in the world. The vector, which was first exposed by Haaretz and Inside Story, exploits the commercial mobile advertising ecosystem to carry out infections.

While technically complex to implement, the attack itself is conceptually simple. The Aladdin system infects the target’s phone by forcing a malicious advertisement created by the attacker to be shown on the target’s phone. This malicious ad could be served on any website which displays ads, such as a trusted news website or mobile app, and would appear like any other ad that the target is likely to see. Internal company materials explain that simply viewing the advertisement is enough to trigger the infection on the target’s device, without any need to click on the advertisement itself.

An operational challenge for the spyware customer or operator is the need to uniquely identify which target device should be shown the malicious ad. Possible target identifiers or selectors could include a known advertising ID, an email address, a geographical location or an IP address. The unique identifier is then used as targeting criteria when creating the malicious advertisement. The identifiers the attackers can use are likely limited technically and operationally to the identifiers supported by the ad network or Demand Side Platform (DSP) used in the Aladdin system.

In practice, leaked documentation indicates that the Aladdin system was designed to use the target’s public IP address as the unique target identifier (Figure 8). When a target is located domestically in a customer country, the Predator operator can request the target’s public IP address from domestic mobile operators, allowing the malicious ad to be targeted accurately to the specific mobile user.

A report from VSquare, an investigative journalism network, suggests Intellexa’s Aladdin vector was under development since at least 2022. Based on analysis of Predator network infrastructure, Amnesty International believes the Aladdin vector was supported in active Predator deployments in 2024, alongside Mars and Jupiter network injection vectors.

Additional Amnesty International technical research, and new reporting from Recorded Future, indicates that Intellexa continues to actively develop their advertising-based infection vector into 2025, using a network of advertising ecosystem companies.

Amnesty International has previously documented the Mars and Jupiter network injection vectors. This new and internal material further substantiates that research and highlights the evolving nature of such vectors, particularly the move to advertising intelligence (ADINT) and advertising-based infections.

Ongoing research and technical investigations by Amnesty International suggest that advertisement-based infection methodologies are being actively developed and used by multiple mercenary spyware companies, and by specific governments who have built similar ADINT infection systems.

Amnesty International believes that the use of such ‘silent’ vectors to deliver browser exploits will continue to grow as targets become increasingly suspicious of unknown links, and as true zero-click attacks become more expensive and technically difficult to achieve. These findings should redouble efforts by technology vendors and the companies active in digital advertising to investigate and disrupt such attacks.

Key finding 2: Intellexa retained direct access to live customer spyware systems

Intellexa’s ability to remotely access and monitor active customer Predator systems is detailed in a highly revealing Intellexa training video conducted over Microsoft Teams. As will be shown, the video suggests that Intellexa staff also had potential access to the most sensitive parts of the customer’s Predator system, including the Predator dashboard and other internal services used to view and store raw surveillance data gathered from targets of the spyware.

A recording of the internal training session, intended for Intellexa support staff, was obtained by the investigative consortium. Intellexa appears to have used Microsoft Teams extensively for internal communications into 2024, shortly before the company was subject to OFAC sanctions.

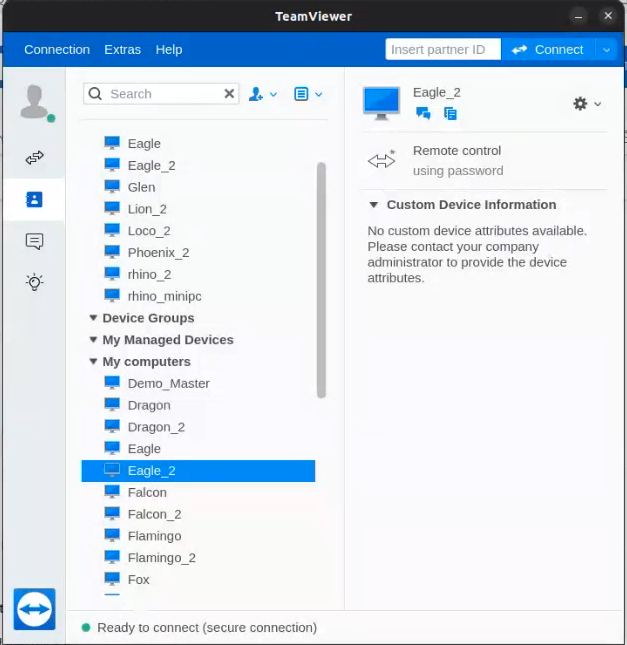

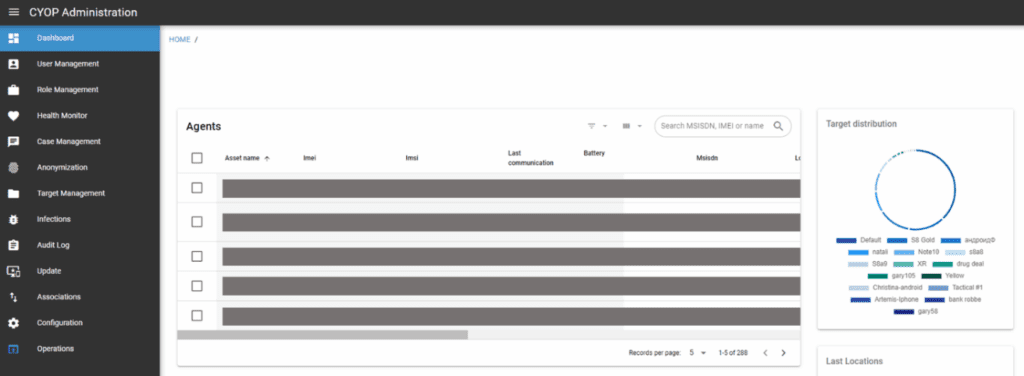

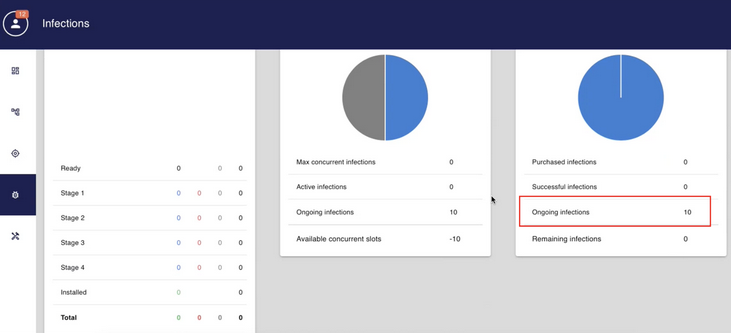

Recorded in mid-2023, the video begins with an instructor connecting directly to a deployed Predator system usingTeamViewer, a commercial remote administration tool. In the video, Intellexa appears to have the ability to remotely access at least 10 different customer systems.

A TeamViewer control panel (Figure 9), briefly visible in the recording, shows at least 10 potential customers. Each is identified with a code name, a standard practice in the cyber surveillance industry to protect customer identities and operational countries. It is unclear if all the customer systems visible in the TeamViewer interface were all still active and online at the time the video was recorded.

The visible customer code names include ‘Dragon’, ‘Eagle’, ‘Falcon’, ‘Flamingo’, ‘Fox’, ‘Glen’, ‘Lion’, ‘Loco’, ‘Phoenix’, ‘Rhino’, as well as one apparent Predator demo system (‘Demo_Master’).

When a staff member asks if they were connecting to a testing environment, the instructor states in the video that they are accessing and viewing a live “customer environment”. Amnesty International believes that the code names represent real customer deployments, and indeed some of the same customer code names are referenced in email communication also visible at points during the same training video.

Intellexa appears to have had access to even more Predator customer systems, but not all were visible in the video. The TeamViewer interface lists customer systems alphabetically in the “My computers” table, but only customers until the letter F are displayed.

Internal Intellexa business records, reviewed during this investigation, show that Intellexa purchased seven licences for the TeamViewer remote desktop software in June 2021. This suggests the company was already using TeamViewer to remotely manage and support deployed customer Predator systems in 2021, well before the video was recorded in 2023. Infrastructure mapping carried out by Amnesty International around September 2021 found seven likely active Predator customers, which is consistent with the number of purchased TeamViewer licences.

Video reveals Intellexa’s deep visibility into live surveillance operations

The video begins with an instructor connecting directly to a remotely deployed, “on-premises” Predator customer system, with codename EAGLE_2, usingTeamViewer.

The video shows the staff member initiating the remote connection, without any indication that the customer or government end-user has reviewed or approved the specific remote connection request. The use of a commercial, non-specialized software like TeamViewer, rather than some form of secure VPN, is also unexpected in such a sensitive surveillance system as it places significant trust in a closed-source software product and the company which develops it.

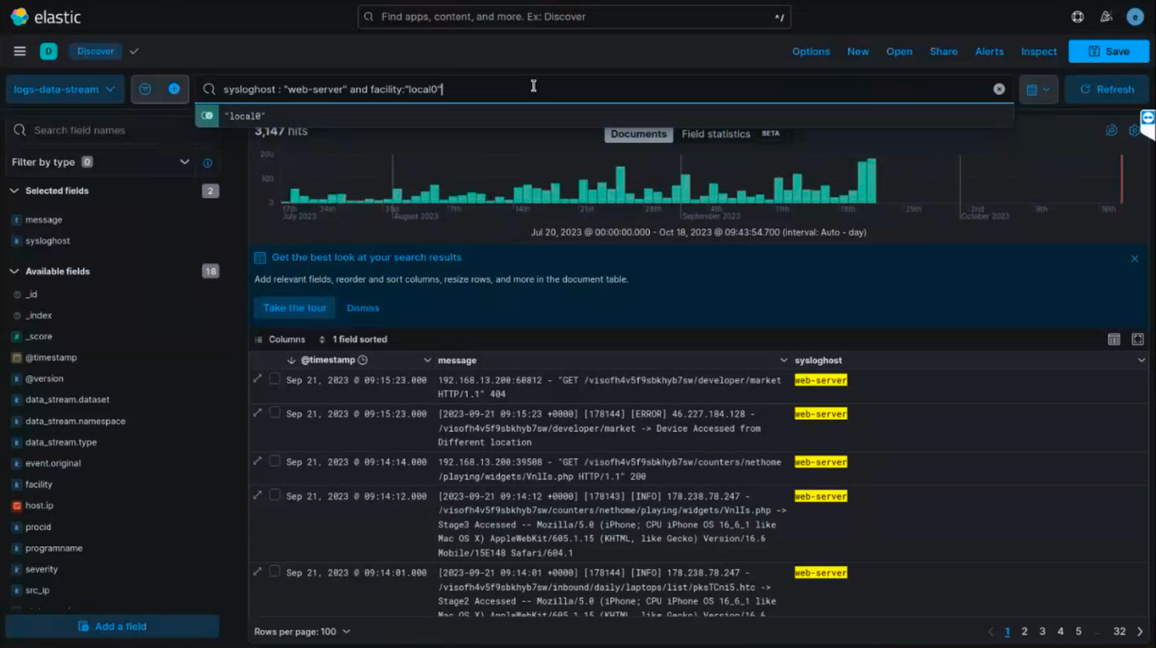

It raises the question of how Intellexa customers, including governments, can review and approve remote connections by Intellexa company staff to the highly sensitive surveillance systems physically hosted in their own countries.

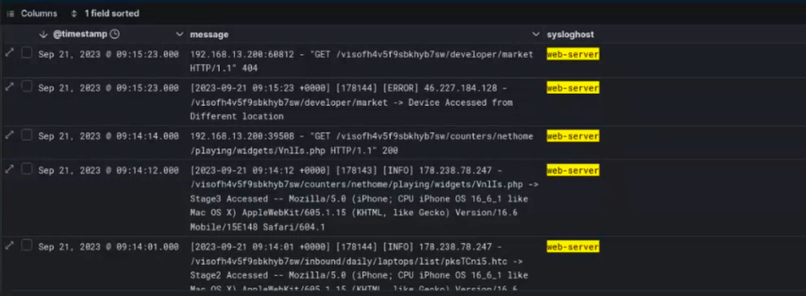

For the next 30 minutes the video continues with an Intellexa staff member browsing an Elasticsearch analytics dashboard, which displays logs and analytics (Figure 10) from various systems and components of the Predator spyware system assigned to a specific customer. The trainer notes that the dashboard includes logs from both the “on-premises” backend systems and the online systems located on the public internet. The dashboard appears to include both live and historical logs. Some log entries were created the same day that the video was recorded, while other search results date from previous weeks.

Various Predator system components are visible in the logging dashboard, including infection servers which deliver exploit links, and command and control (CNC) servers responsible for forwarding surveillance data back to the customer.

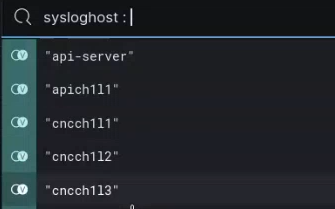

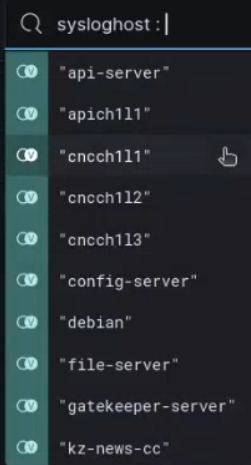

Intellexa uses multiple layers of servers in an attempt to hide the trail connecting their customer and the Predator backend systems, making it difficult for victims and researchers to scrutinize. Each CNC server is configured in a three-level chain with a unique name (shown in Figure 11) representing the chain and the layer of the server. The first (public) server in CNC chain 1 is labelled “cncch1l1”. The server in the second layer of chain 1 is labelled “cncch1l2” and so on.

The dashboard also included logs from the Predator URL shortener and infection servers (similarly labelled “urlch1l1”), as well as from other systems named “file-server”, “api-server” and “config-server”. These are internal services used to deploy and manage components of the Predator infection system. It is unclear if the customer in question approved for their logs and analytics to be used and shared for training purposes.

Logs provide direct visibility into live surveillance operations

In addition to technical logs from the various system components, the video also shows what appears to be live (“in-the-wild”) Predator infection attempts against real targets of the Intellexa customer. Detailed information is shown from at least one infection attempt against a target in Kazakhstan, visible in Figure 12. The visible logs include the infection URL, the target’s IP address, and the software versions of the target’s phone. The infection process itself apparently failed.

The phone number of the actual target is not visible in the infection server logs shown in the video, and this specific information about the target would not necessarily be stored in infection servers.

However, data visible in the log dashboard indicates that logs from other internal Predator backend system components are also accessible, including those storing targeting information.

During the training video, it becomes apparent that Intellexa staff are not limited to remotely accessing a narrow set of log files, instead having privileged access to the core backend network of the customer system, including the network containing targeting information and collected surveillance data.

Indications that Intellexa staff could also access the Predator customer dashboard and other internal backend services

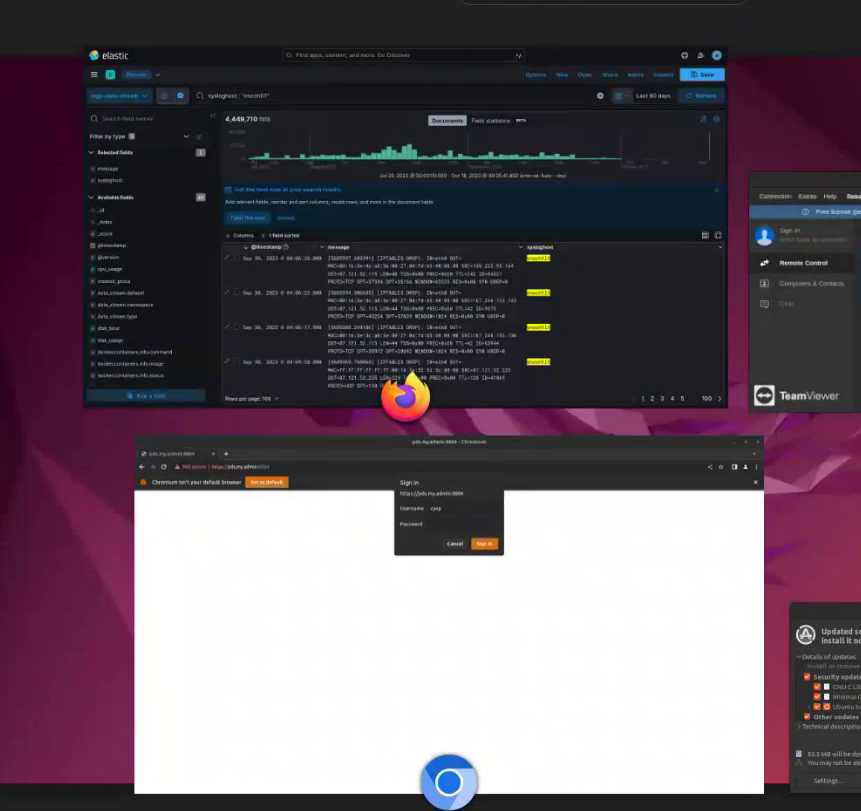

The instructor accessed the ElasticSearch log dashboard from a web browser running on an Ubuntu desktop running on the customer backend network. The Intellexa staff connected directly to this backend Ubuntu computer which was running TeamViewer.

During the training, the instructor switches windows on the Ubuntu desktop, which reveals the other applications open on the remote computer.

During this point, a separate open Chrome window is revealed which displays a login prompt for a system hosted at https://pds.my.admin:8884. The username “cyop” is prefilled indicating the remote computer used by Intellexa staff to view system logs, has also previously logged into the PDS system.

Based on prior research, and new material included in the leak, Amnesty International concludes that the login prompt shown in the training video is for a customer’s Predator dashboard (Figure 15), the main control panelused by customers to conduct surveillance operations including adding targets, creating new infection links, and viewing surveillance data ultimately collected from victims of the spyware.

The customer targeting dashboard is referred to in internal Intellexa documentation by various names. These include: Predator Delivery Studio (“PDS”), Helios Delivery Studio (“HDS”) and the Cyber Operations Platform (“CyOP”). Notably both terms, PDS and CyOP, are included in the URL and the username field from the training video. The non-public ”my.admin” domain is used for various internal services in the Predator system, particularly the on-premises backend systems.

The fact that the remote desktop system used by Intellexa support staff can even connect to the Predator dashboard raises alarming questions about the degree of compartmentalization of live surveillance data and targeting from the company and its staff.

Mercenary spyware systems have inherent technical and operational complexities. It is understandable, and not unexpected, that Intellexa would need some ability to connect remotely to customer systems to debug and repair technical issues as they occur.

However, in whole, the video suggests Intellexa staff retained deep access to live customer systems, with capabilities extending far beyond those necessary to view limited technical logs or to diagnose problems on the system. This remote access, via TeamViewer, appears to have been possible without apparent oversight from their customers.

Most strikingly, the video shows that Intellexa staff were able to open the customer Predator targeting dashboard, revealing privileged network access to the most sensitive parts of the Predator system, including dashboard, but also the storage system containing photos, messages and all other surveillance data gathered from victims of the Predator spyware.

These findings can only add to the concerns of potential surveillance victims. Not only is their most sensitive data exposed to a government or other spyware customer, but their data risks being exposed to a foreign surveillance company, which has demonstrable issues in keeping their confidential data stored securely.

Key finding 3: Leaked logs confirm attribution of supected infection domains and infrastructure to Predator

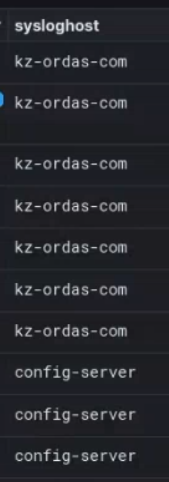

At multiple points during the training video, the Predator infection domains kz-news[.]cc and kz-ordas[.]com are shown. These domains imitate legitimate Kazakhstani news websites and are designed to trick users to click unwittingly on a Predator infection link.

Amnesty International had previously identified both kz-news[.]cc and kz-ordas[.]com as Predator infection domains through independent technical tracking of active Predator infection servers. Sekoia, a French cybersecurity company, had similarly identified and publicly documented kz.new[.]cc, alongside numerous other Predator infection domains.

This new evidence from this leak conclusively confirms the attribution of these domains to Intellexa’s Predator spyware. It also validates the methodology used by Amnesty International and other civil society and industry partners to identify Predator attack infrastructure over many years, from first public exposure in 2021 until the present.

Both domains imitate legitimate Kazakhstani news websites. The training video also showed that the same customer Predator system was used to target devices in Kazakhstan. Accordingly, Amnesty International attributes both of these domains, and the EAGLE customer system, to Kazakhstan. Amnesty International has previously named Kazakhstan as a government customer of Intellexa in the Predator Files, which has been affirmed by independent research from Recorded Future.

While no victims of Predator spyware targeting have been identified in Kazakhstan, previous investigations by the Security Lab have documented the unlawful hacking of at least four Kazakhstani youth activists with Pegasus spyware in 2021.

Key finding 4: Files strengthen forensic evidence linking Predator spyware to surveillance abuses in Greece and Egypt

The leak also contains important technical information which confirms the forensic attribution of numerous suspected cases of Predator surveillance to Intellexa and their spyware customers.

An internal document named “OPSEC” (operational security) details steps Intellexa has taken to frustrate the efforts of forensic investigations, including the company’s attempt to obscure the technical links between the Predator spyware and the company itself.

The internal technical documentation, created in 2020, lists key indicators of compromise including on-device filenames, configuration options and defensive mechanisms built into the contemporaneous Predator spyware agent code. The version of the Predator agent used at the time was written in Python. Much of the agent code and configuration options were shared by both the Android and iOS versions of the agent.

| OPSEC This page’s aim is to bring forward and discuss all opsec related features and concepts incorporated in Predator. It will also document all necessary opsec adjustments we need to ensure we have before delivering Predator to customers. Storage RSA Key As the storage module documentation specifies, the storage’s AES key is encrypted using an RSA public key, configured in the RSA_PKEY key in the CFG dictionary, hardcoded into the Python library. The matching private key is used by the C2 server in order to decipher the hello message and retrieve the AES key for the storage. Different customers (Falcon, Goal, etc.) should each have its own key pair, so even if one customer is breached or compromised, the rest stay protected. Priorities and Their Meaning Predator’s storage supports 3 different priorities, which differ not only by what information is exfiltrated first, but mostly by what information is leaked when. It is also important to note at this point that files have the lowest priority (unless collected immediately). Theoretically, there is a simple way to add any kind of restrictions, parameters and criteria according to which the current priority, hence the lowest priority from which data will be exfiltrated at a specific point in time (see the storage module documentation for more information). Effectively, at the time this document is compiled (July 2020), there are three criteria taken into consideration: current battery level, charger status (connected or not) and network type (cellular or WiFi). The priorities mechanism is a self-defense mechanism that protects Predator from using too much cellular data or creating too much traffic. This is in order to “stay under the radar” and make it more difficult to be recognized. Using too much of the device resources (network or power) may very well arise the suspicion of a target, which might lead to the discovery of Predator on the device. fs.db Passphrase fs.db is a sqlite database file encrypted using the sqlite extension sqlcipher. In order to encrypt the database, we use a passphrase at build time, and this passphrase must be known to the Python library. This value is configured in the FS_KEY key in the pred_config configuration dictionary. Mismatch between the passphrase used to compile fs.db and in the FS_KEY key will prevent Predator from functioning. Assuming each customer has one Python library and one fs.db, each client should have its own passphrase. Storage Limits The storage module has configurable limits for the sizes of the different priorities, in order to make sure the collected data doesn’t exhaust the device’s storage capacity. Exhaustion of the device’s storage can definitely arise the suspicion of a justly paranoid target. Read more on the storage limit in Storage module’s documentation. Guard The guard module is responsible for protecting Predator from being detected by a forensic investigator. The module will self destruct Predator on predefined cases. Also, in case the self-destruction had happened, the guard will report the reason. It is crucial that the guard is active when in production use. C2 Message Boundaries Because the size of the messages sent to the server might be big, we use multipart content-type, and therefore we use boundaries. The boundaries are predefined on the Predator clients and the C2, and might be used to detect Predator, in scenarios such as SSL Striping or when we don’t pin the C2 certificate, and a fake C2 is used to examine Predator. It is therefore recommended to set different boundaries for each customer. IS Certificate on pred.so If the Infection Server certificate is not pinned, make sure it isn’t included (hence defined) in the library. It both enlarges the library size and provide information to forensic researchers that might allow to establish connection between different customers. |

Unfortunately for Intellexa, the same document in the hands of spyware accountability researchers provides crucial evidence, a forensic Rosetta stone, to conclusively trace suspected Predator attacks, and Predator spyware samples and exploits discovered in-the-wild, back to the company.

Notably, all filenames and configuration options listed in the internal OPSEC page were also present in the Android and iOS Predator samples identified by researchers at Citizen Lab. These samples were found while Citizen Lab investigated a Predator campaign targeting multiple individuals with connections to Egypt, including the prominent Egyptian political activist Ayman Nour.

The identical nature of the configuration options listed in both Intellexa’s internal 2020 Predator documentation, and the spyware samples found used in Egypt, prove categorically that Intellexa’s Predator was used in the Egyptian attacks. It also confirms the attribution of indicators of compromise (IOCs; associated network domains and infrastructure) used in that campaign to a customer of Intellexa’s spyware product.

| OPSEC Page strings | ITW iOS Config | ITW Android Config | Notes |

| RSA_PKEY | RSA_PKEY | RSA_PKEY | RSA public key used to encrypt C2 communications |

| FS_KEY | FS_KEY | FS_KEY | Key used to encrypt SQLite database |

| fs.db | /private/var/logs/keybagd/fs.db | /data/local/tmp/wd/fs.db | Filename for encrypted SQLite database containing additional code and modules. |

| pred.so | N/A (Only used on Android) | /data/local/tmp/wd/pred.so | Filename of Predator shared library on Android |

The 2021 Citizen Lab report also documented forensics artifacts found on an Egyptian iPhone infected with Predator. The iPhone was infected after connecting to distedc[.]com, the same server from which Citizen Lab obtained the Predator Android and iOS samples.

The Citizen Lab report lists specific forensic traces found on the Egyptian phone, which Amnesty International also independently attributes as indicators of Predator infection. The IOCs include traces of two Predator spyware processes running from a specific path on the infected device.

Amnesty International has seen other Predator attacks with identical forensic traces of infection, including on the device of Greek journalist Thanasis Koukakis, whose phone was targeted with Predator in 2020 and 2021. Koukakis’s phone showed evidence of process names “UserEventAgent” and “com.apple.WebKit.Networking” running from the same “/private/var/tmp/” directory, also seen by Citizen Lab in the Egyptian case. Legitimate Apple processes do not run from this directory.

| Predator indicators of compromise (IOCs) from iPhone infections in Egypt (2021) | Predator IOCs from Thanasis Koukakis case in Greece (2021) |

/private/var/tmp/UserEventAgent | /private/var/tmp/UserEventAgent |

/private/var/tmp/com.apple.WebKit.Networking | /private/var/tmp/com.apple.WebKit.Networking |

In their reports, Citizen Lab have already attributed the 2021 attacks in Egypt and Greece to Intellexa’s Predator, drawing on evidence from forensic analyses of the victim’s devices. Amnesty International is now able to add to that evidence, drawing on Intellexa’s own documentation of its spyware. Amnesty International also attributes these attacks to Intellexa’s Predator spyware with high confidence.

What these findings mean for spyware accountability efforts

Despite years of public exposure, legal cases, and financial sanctions against Intellexa and individuals linked with the company, the recently uncovered Predator spyware attacks show that the human rights abuses powered by the company are ongoing. The attempted Predator attack against a human rights lawyer in Pakistan in summer 2025 is a grave violation of the rights to privacy and freedom of expression, and puts at risk the right to effective remedy and fair trial.

Throughout this period, Intellexa has been able to maintain access to the latest zero-day exploits, while also expand the suite of infection vectors. Most concerningly, is the evidence that Intellexa has developed and deployed ‘Aladdin’, a system to silent infect target phones, just by viewing a malicious digital ad. Evidence that Intellexa is subverting the digital advertising ecosystem to hack phones, demands urgent attention and action from the advertising (AdTech) industry to disrupt these attacks, and harms from the abuse of targeted advertising more broadly.

The current investigation also provides one of the clearest and most damning views yet into the internal operations and technology of this mercenary spyware company. Leaked materials allow us to confidently establish attribution of previous suspected Predator spyware attacks to Intellexa and customers of their Predator spyware. This includes the attack on Greek investigative journalist Thanasis Koukakis.

Even more alarmingly, the materials reveal that Intellexa, at least in certain instances, had the technical capability to remotely access the spyware systems of its customers after installation and live deployment. Mercenary spyware companies are typically keen to state that they do not have access to the surveillance systems once they have been installed for their government customers. For example, in a letter to the European Data Protection Supervisor in 2023, NSO Group stated that “[i]mportantly, NSO does not operate Pegasus and is not privy to the data collected”. It is likely that government customers expect their systems and data not to be accessible to the company to keep their operations strictly confidential. However, such a separation between the manufacturer of spyware and its direct operations can be important from a legal perspective. If a mercenary spyware company is found to be directly involved in the operation of its product, it could potentially leave them open to claims of liability in cases of misuse.

To keep surveillance operations at arm’s length, the customer’s surveillance systems are typically installed physically in the customer country, where they are operated by a government customer. The government operator then has full control of the system, the collected evidence and the targeting and surveillance operations, without access by the company.

This investigation exposes how Intellexa, in at least some cases, had remote access capabilities, allowing company staff to see and share logs and technical details from live customer surveillance operations. As outlined above, the training video for Intellexa staff appears to demonstrate the capacity to remotely access the surveillance systems of several clients, though it is not possible to infer from this that such remote access was available to Intellexa for all clients, or at all times. Remote access capabilities, even those intended for remote technical support and maintenance, raise questions about the degree of operational separation. The additional evidence that Intellexa support staff could also access further internal Predator customer systems – without evident technical limitations – deepens concerns about what security boundaries were in place to isolate the spyware company from its customers’ data and operations.

In a letter sent to Intellexa on 26 November outlining these findings, Haaretz asked whether Intellexa had access to customer surveillance systems after deployment; whether such access was approved by customers; and whether there were any technical limitations on their access. On 3 December, a legal representative acting on behalf of Tal Dilian, the founder of Intellexa, sent a written response to Haaretz that states that he has “not committed any crime nor operated any cyber system in Greece or anywhere else”.

Questions about Intellexa’s specific legal responsibilities for its customers’ use of its spyware are at the heart of an ongoing criminal case in Greece, where four individuals are on trial (including three people linked with Intellexa) for “violating telephone communication secrecy”. The trial focuses on the use of Predator spyware to hack smartphones of a range of individuals in Greece, including Thanasis Koukakis, the Greek investigative journalist.

The finding that Intellexa had potential visibility into active surveillance operations of their customers, including seeing technical information about the targets, raises new legal questions about Intellexa’s role in relation to the spyware and the company’s potential legal or criminal responsibility for unlawful surveillance operations carried out using their products.