Summary

- We have identified several campaigns of credentials phishing, likely operated by the same attackers, targeting hundreds of individuals spread across the Middle East and North Africa.

- In one campaign, the attackers were particularly going after accounts on popular self-described “secure email” services, such as Tutanota and ProtonMail.

- In another campaign, the attackers have been targeting hundreds of Google and Yahoo accounts, successfully bypassing common forms of two-factor authentication.

Introduction

From the arsenal of tools and tactics used for targeted surveillance, phishing remains one of the most common and insidious form of attack affecting civil society around the world. More and more Human Rights Defenders (HRDs) have become aware of these threats. Many have taken steps to increase their resilience to such tactics. These often include using more secure, privacy-respecting email providers, or enabling two-factor authentication on their online accounts.

What is phishing?Credentials phishing consists in the creation of a website that imitates the login prompt of a given online service, such as Gmail or Facebook, with the objective of luring a victim into visiting the malicious page and entering their username and passwords, thereby transmitting these credential to the attackers. |

However, attackers too learn and adapt in how they target HRDs. This report documents two phishing campaigns that Amnesty International believes are being carried out by the same attacker (or attackers) likely originating from amongst the Gulf countries. These broad campaigns have targeted hundreds, if not a thousand, HRDs, journalists, political actors and others in many countries throughout the Middle East and North Africa region.

What makes these campaigns especially troubling is the lengths to which they go to subvert the digital security strategies of their targets. The first campaign, for example, utilizes especially well-crafted fake websites meant to imitate well-known “secure email” providers. Even more worryingly, the second demonstrates how attackers can easily defeat some forms of two-factor authentication to steal credentials, and obtain and maintain access to victims’ accounts. As a matter of fact, Amnesty Tech’s continuous monitoring and investigations into campaigns of targeted surveillance against HRDs suggest that many attacker groups are developing this capability.

Taken together, these campaigns are a reminder that phishing is a pressing threat and that more awareness and clarity over appropriate countermeasures needs to be available to human rights defenders.

Phishing Sites Imitating “Secure Email” Providers

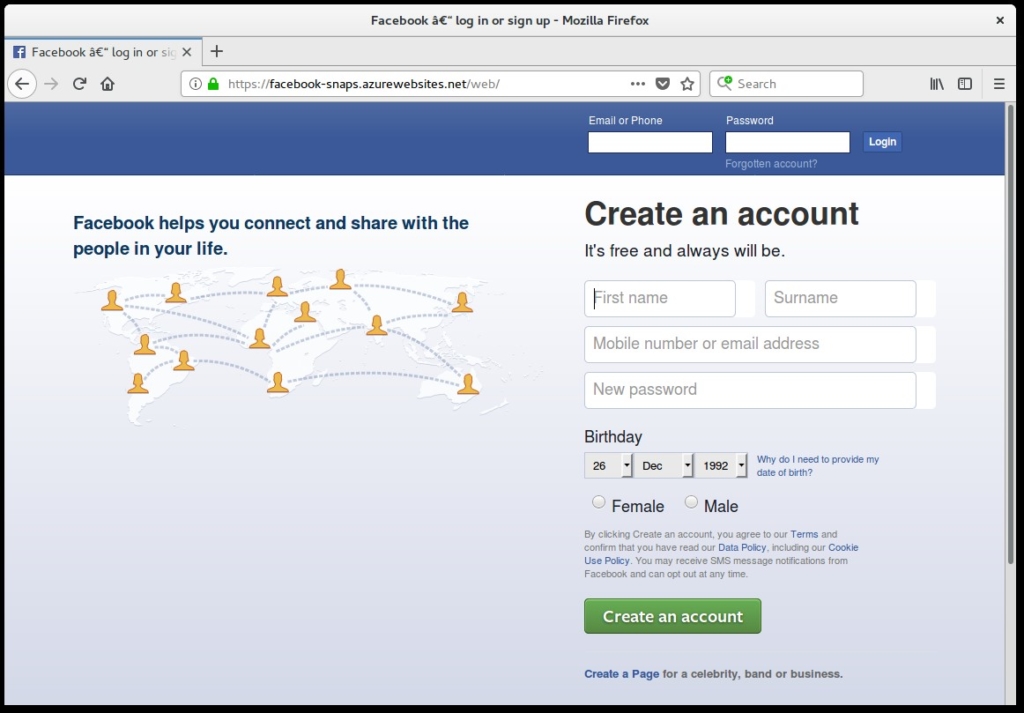

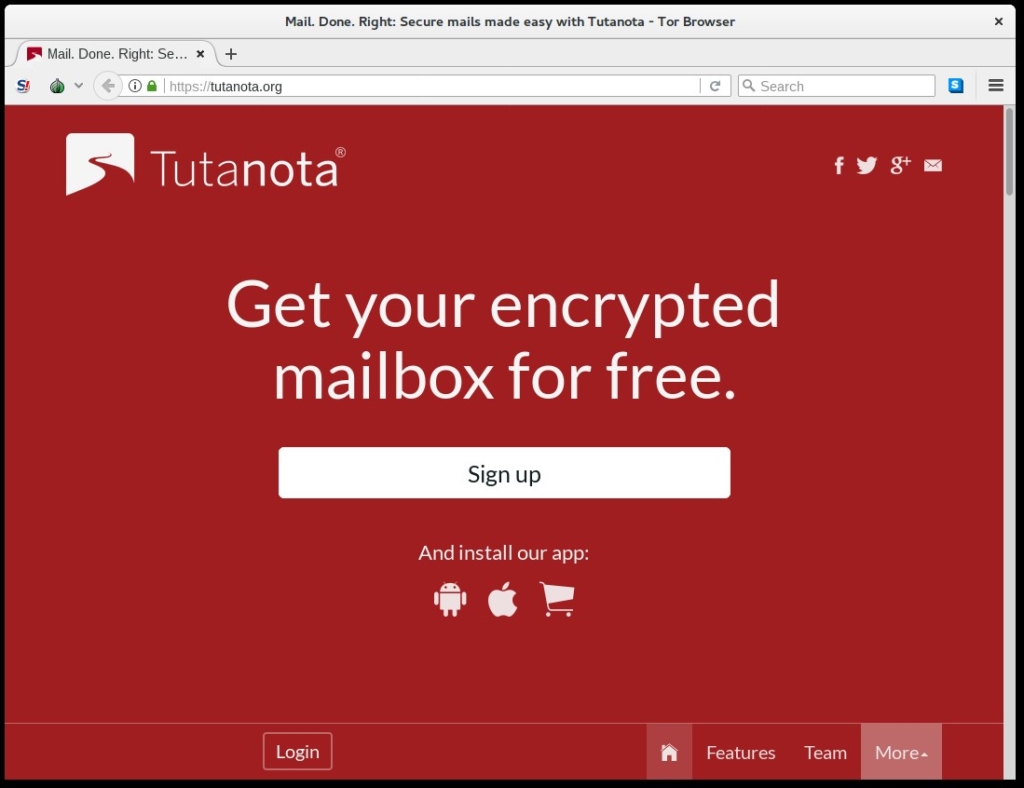

Amnesty International has identified several well-crafted phishing sites for the popular email services Tutanota and ProtonMail. The providers are marketed as “secure email” solutions and have consequently gained some traction among activists.

These sites contain several elements that make them especially difficult for targets to identify as fakes. For instance, the attackers managed to obtain the domain tutanota.org and used it to almost completely replicate the original website for the Tutanota service, which is actually located at tutanota.com.

Many users rightfully expect that online services control the primary .com, .org and .net domain variants of their brand. If an attacker manages to acquire one of these variants they have a rare opportunity to make the fake website appear significantly more realistic. These fake sites also use transport encryption (represented by the https:// prefix, as opposed to the classic, unencrypted, https://). This enables the well-recognized padlock on the left side of the browser’s address bar, which users have over the years been often taught to look for when attempting to discern between legitimate and malicious sites. These elements, together with an almost indistinguishable clone of the original website, made this a very credible phishing site that would be difficult to identify even for the more tech-savvy targets.

If a victim were tricked into performing a login to this phishing site, their credentials would be stored and a valid login procedure would be then initiated with the original Tutanota site, giving the target no indication that anything suspicious had occurred.

Because of how remarkably deceptive this phishing site was, we contacted Tutanota’s staff, informed them about the ongoing phishing attack, and they quickly proceeded to request the shutdown of the malicious infrastructure.

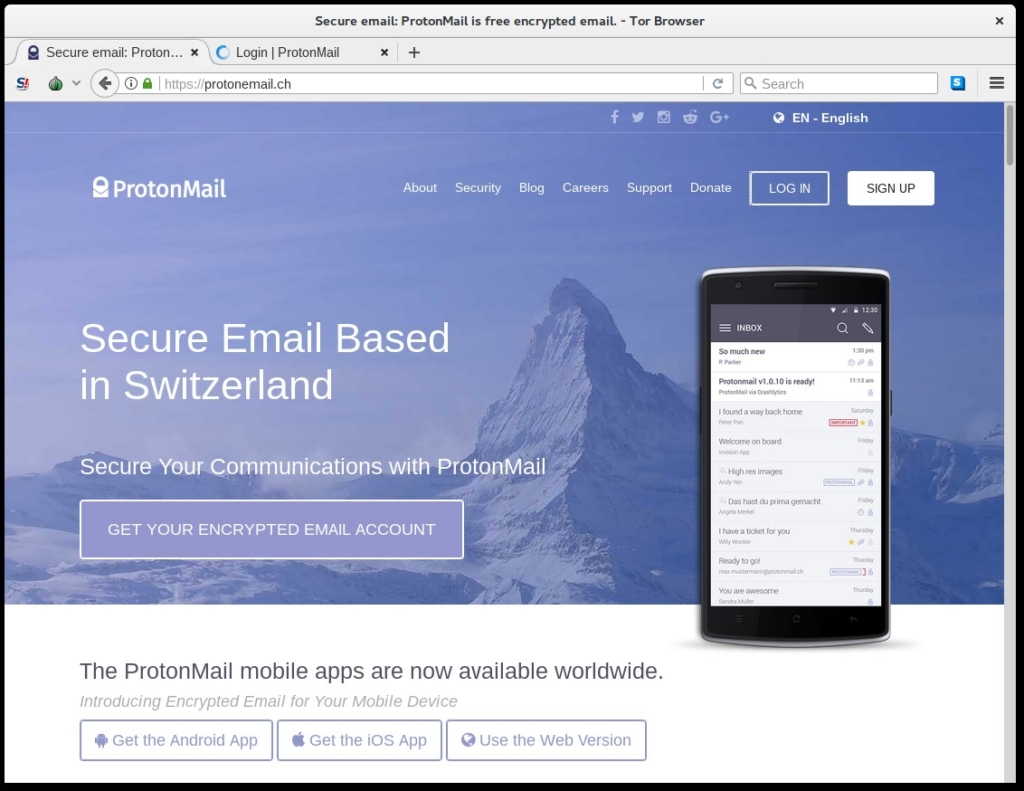

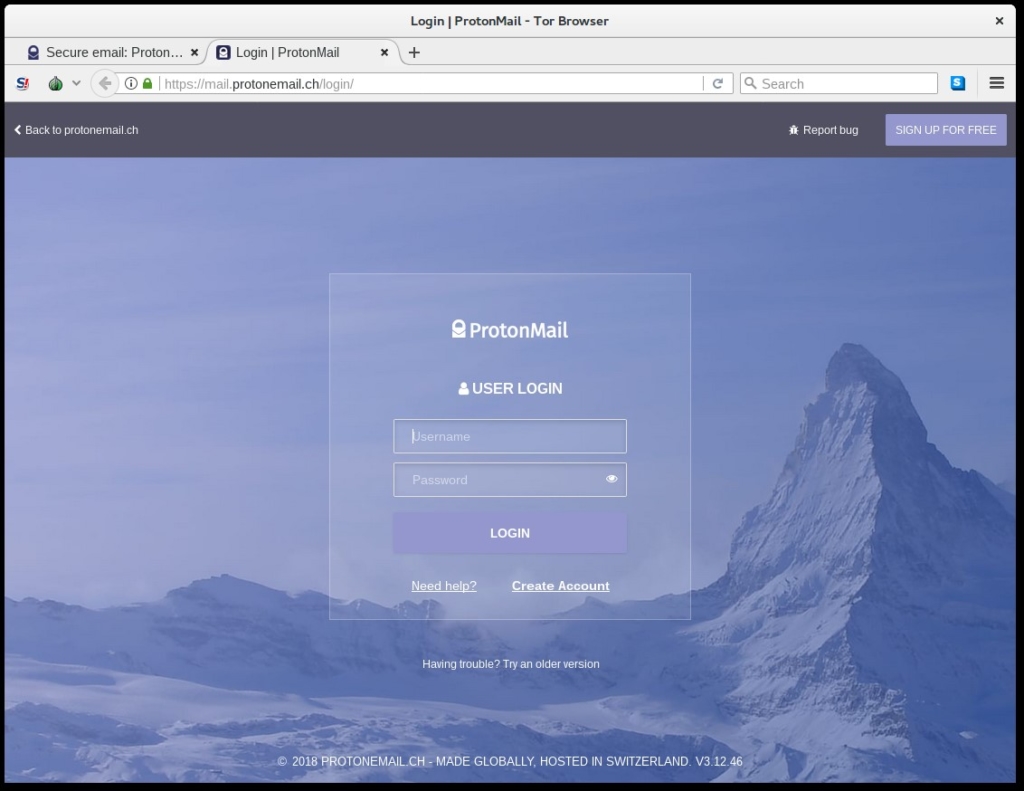

These same attackers were also operating a ProtonMail phishing website (another popular email service marketed as secure) located at protonemail.ch, where the additional letter “e” is all that distinguishes this well-built replica from the original valid website protonmail.ch.

Clicking on the “LOG IN” button would direct the victims to the fake login prompt.

Of course, compiling and submitting the login form would result in the account’s credentials being stolen by the attackers.

Widespread Phishing of Google and Yahoo Users

Throughout 2017 and 2018, human rights defenders and journalists from the Middle East and North Africa region have been sharing with us suspicious emails they have been receiving. Investigating these emails, we identified a large and long-running campaign of targeted phishing attacks that has targeted hundreds, and likely over one thousand people overall. Most of the targets seemingly originating from the United Arab Emirates, Yemen, Egypt and Palestine.

It is worth noting that we found this campaign to be directly connected to some attacks included in section 2.4.2 of a technical report by UC Berkeley researcher Bill Marczak, in which he suggests various overlaps with other campaigns of targeted surveillance specifically targeting dissidents in the UAE.

Our investigation leads us to additionally conclude that this campaign likely originates with the same attacker – or attackers – who cloned the Tutanota and ProtonMail sites in the previous section. As in the previous campaign, this targeted phishing campaign employs very well-designed clones of the commercial sites it impersonates: Google and Yahoo. Unlike that campaign, however, this targeted phishing campaign is also designed to defeat the most common forms of two-factor authentication that targets might use to secure their accounts.

Lastly, we have identified and are currently investigating a series of malware attacks that appear to be tied to these phishing campaigns. This will be the subject of a forthcoming report.

Fake Security Alerts Work

In other campaigns, for example in our Operation Kingphish report, we have seen attackers create well developed online personas in order to gain the trust of their targets, and later use more crafty phishing emails that appeared to be invites to edit documents on Google Drive or participating in Google Hangout calls.

In this case, we have observed less sophisticated social engineering tricks. Most often this attacker made use of the common “security alert” scheme, which involves falsely alarming the targets with some fake notification of a potential account compromise. This approach exploits their fear and instills a sense of urgency in order to solicit a login with the pretense of immediately needing to change their password in order to secure their account. With HRDs having to be constantly on the alert for their personal and digital security, this social engineering scheme can be remarkably convincing.

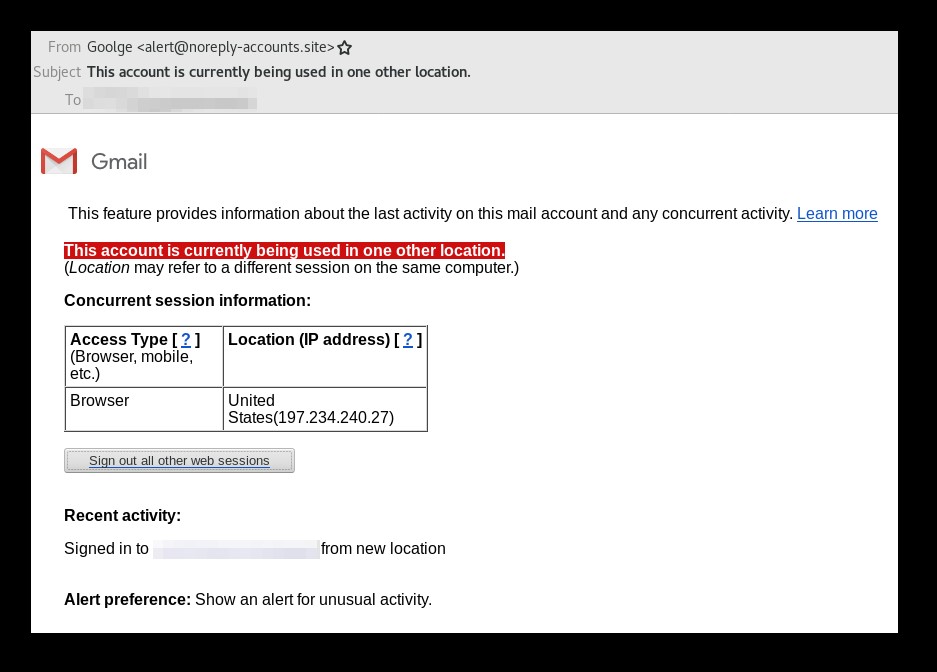

The following is one example of a phishing email sent by this attacker.

Another phishing email sent with a similar variation of the same social engineering scheme.

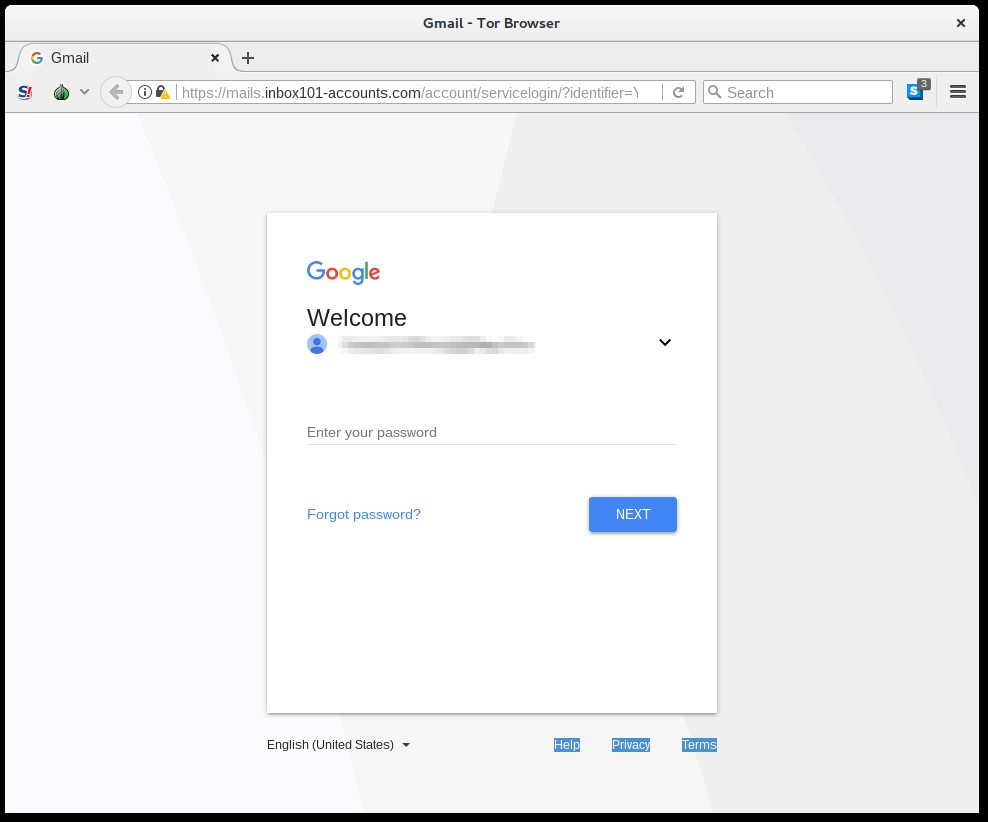

Clicking on the links and buttons contained in these malicious emails would take the victim to a well-crafted and convincing Google phishing website. These attackers often and regularly create new sites and rotate their infrastructure in order to avoid detection and reduce the damage of unexpected shutdowns by domain registrars and hosting providers. You can find at the bottom of this report a list of all the malicious domains we have identified.

Although less common than attacks impersonating Google, we have also observed phishing attacks targeting Yahoo users.

How Does the Phishing Attack Work?

In order to verify the functioning of the phishing pages we identified, we decided to create a disposable Google account. We selected one of the phishing emails that was shared with us, which pretended to be a security alert from Google, falsely alerting the victim of suspicious login activity, and soliciting them to change the password to their account.

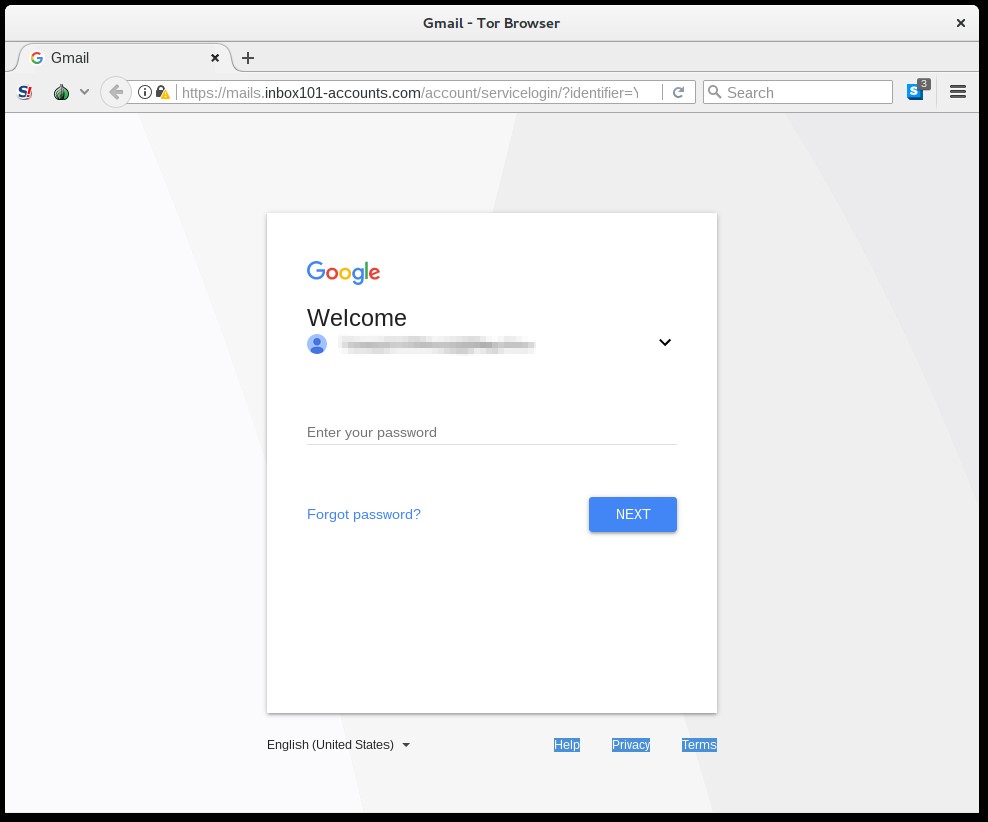

The first step was to visit the phishing page.

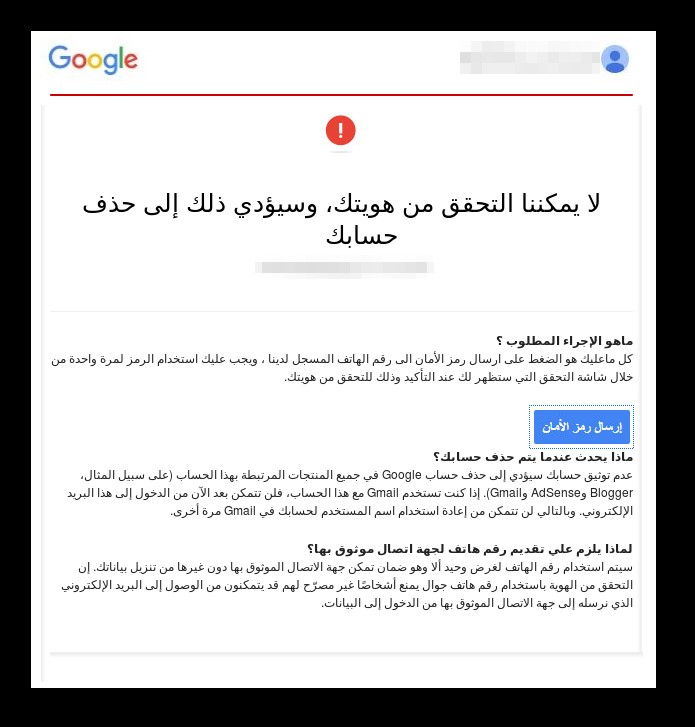

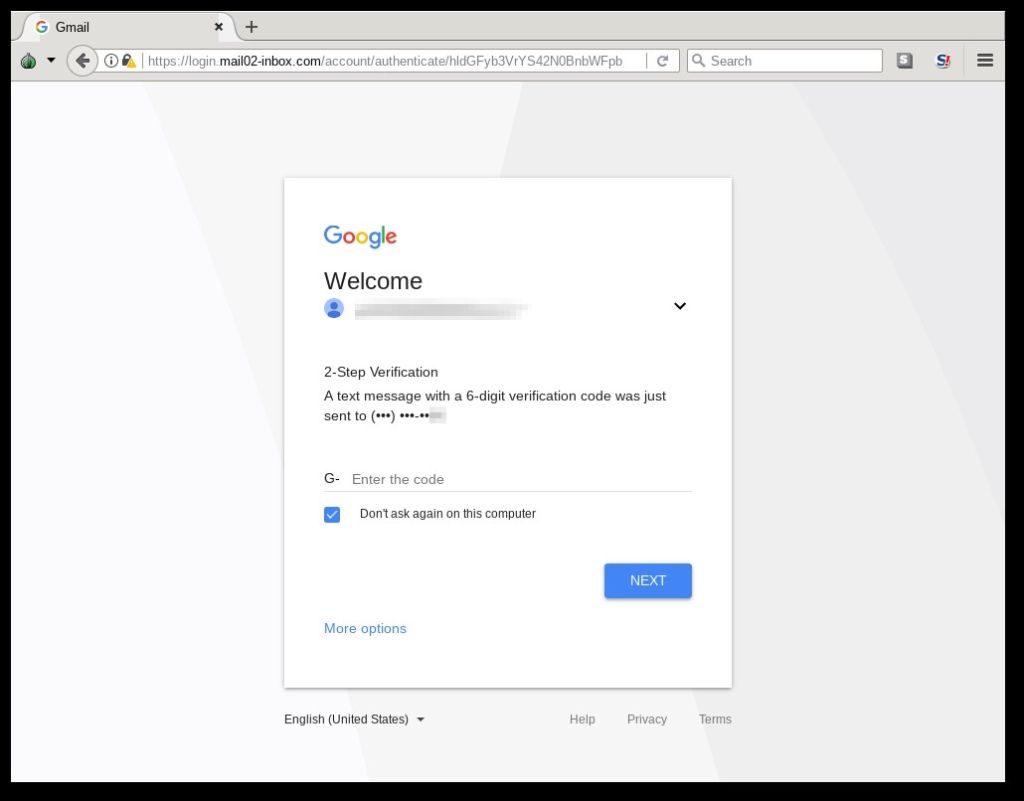

When we logged into the phishing page, we were redirected to another page where we were alerted that we had been sent a 2-Step Verification code (another term for two-factor authentication) via SMS to the phone number we used to register the account, consisting of six digits.

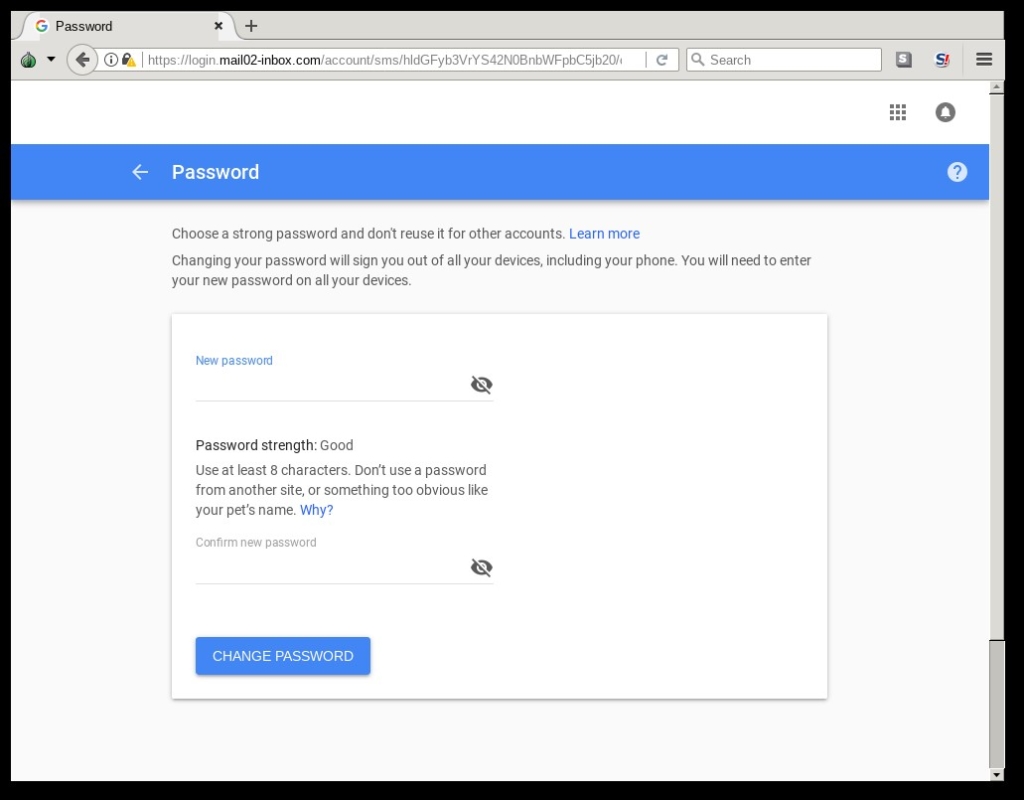

Sure enough, our configured phone number did receive an SMS message containing a valid Google verification code. After we entered our credentials and the 2-Step Verification code into the phishing page, we were then presented with a form asking us to reset the password for our account.

To most users a prompt from Google to change passwords would seem a legitimate reason to be contacted by the company, which in fact it is.

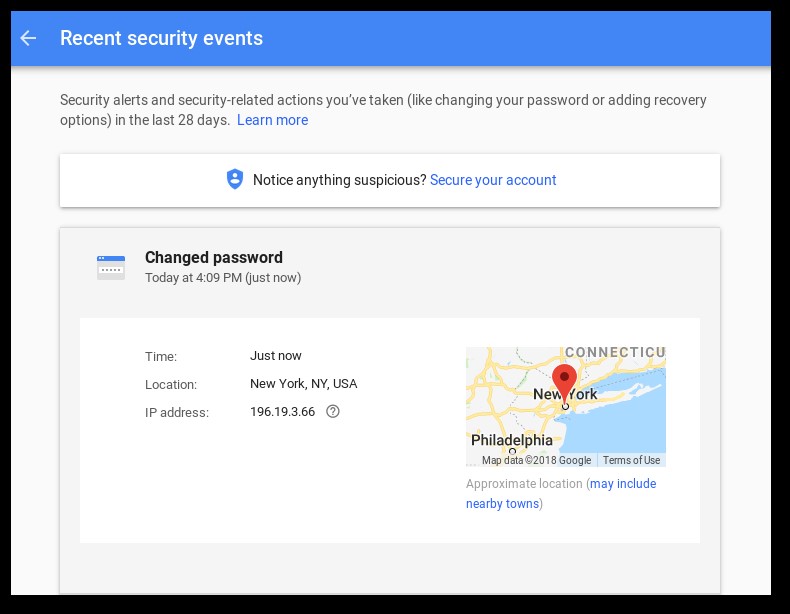

After checking the security events on our disposable Google account, we noticed that a password change was in fact issued by Windows computer operated by the attackers, seemingly connecting from an IP address that Google geolocates within the USA.

(The IP address used by the attackers to automatically authenticate and modify our Google account, 196.19.3.66, is actually an unauthenticated Squid HTTP proxy. The attackers can use open proxies to obscure the location of their phishing server.)

The purpose of taking this additional step is most likely just to fulfill the promise of the social engineering bait and therefore to not raise any suspicion on the part of the victim.

After following this one last step, we were then redirected to an actual Google page. In a completely automated fashion, the attackers managed to use our password to login into our account, obtain from us the two-factor authentication code sent to our phone, and eventually prompt us to change the password to our account. The phishing attack is now successfully completed.

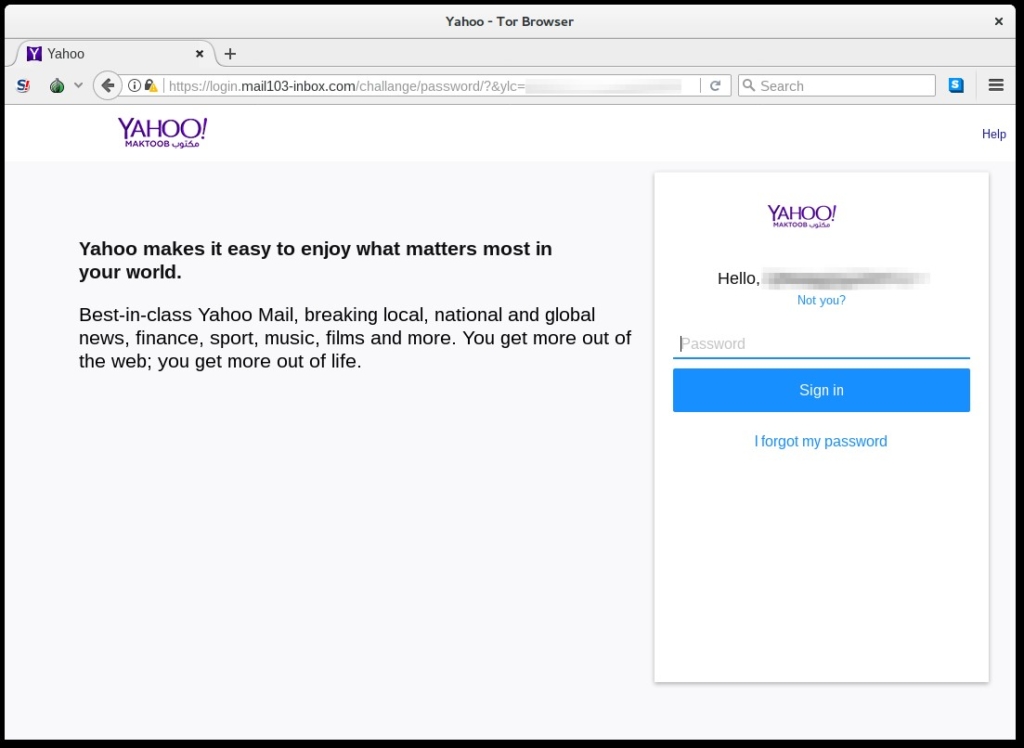

Similarly, we created a new Yahoo account and configured two-factor authentication using the available phone verification as visible in the account settings:

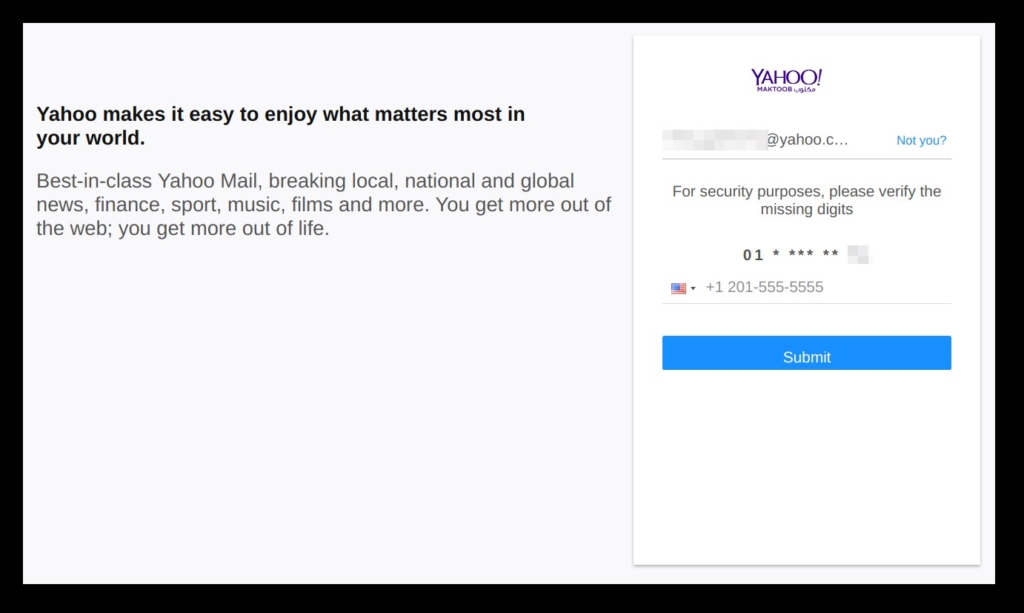

After entering our newly created email address and password in the Yahoo phishing page operated by the attackers we are first requested to verify the phone number associated with our account.

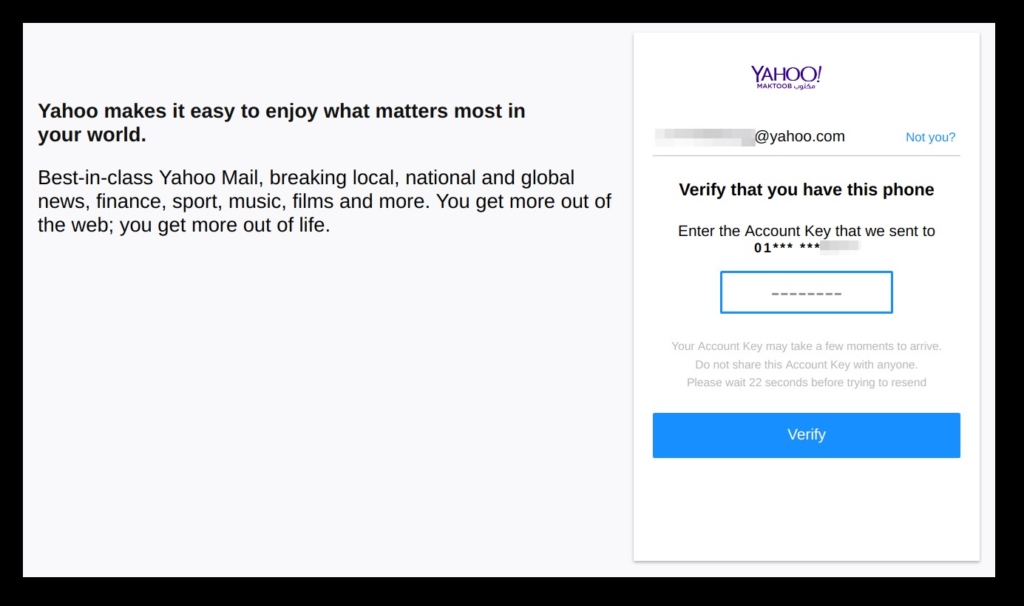

Then we are requested to enter the verification code that would be sent to our phone.

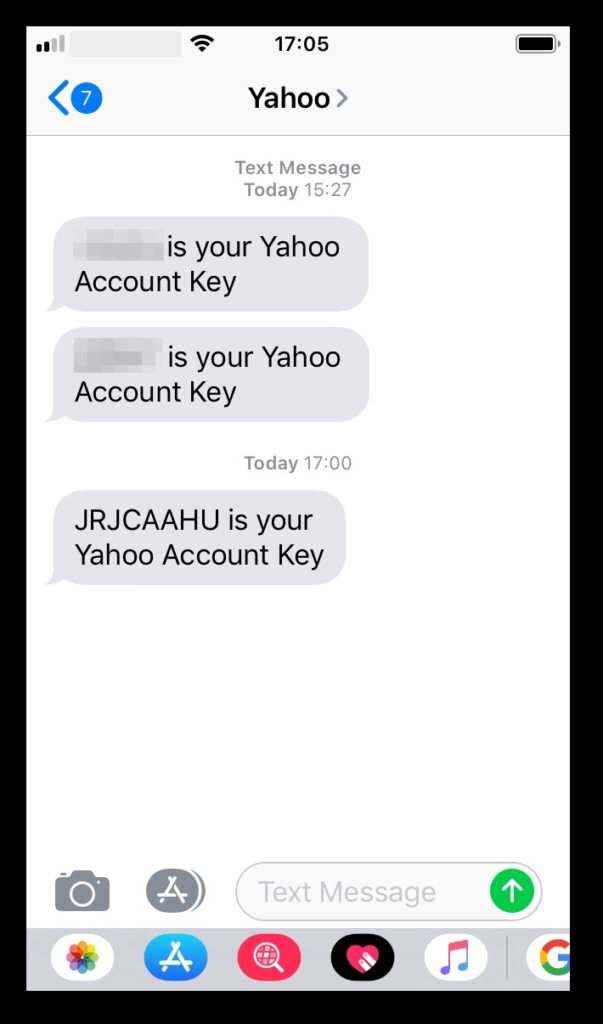

Indeed, we received a valid verification code from Yahoo.

Challenges in Securing Online Accounts

Finding a secure way to authenticate users is a very difficult technical issue, although some progress has been made over the years that has raised the bar of difficulty for attackers attempting to compromise accounts at scale.

Two-factor authentication has become a de-facto standard that is almost always recommended as a required step for securing online accounts. With two-factor authentication procedures enabled, users are required to provide a secondary form of verification that normally comes in the form of a numerical token that is either sent via SMS or through a dedicated app to be installed on their phone. These tokens are short-lived, and normally expire after 30 seconds. In other cases, like that of Yahoo, the user is required instead to manually allow an ongoing authentication attempt by tapping a button on their phone.

Why is this useful? Requiring a secondary form of authentication prevents some scenarios in which an attacker might have obtained access to your credentials. While this can most commonly happen with some unsophisticated phishing attempts, it is also a useful mitigation to password reuse. You should definitely configure your online accounts to use different passwords (and ideally use a password manager), but in the case you reuse – accidentally or otherwise – a password which was stolen (for example through the numerous data breaches occurring all the time) having two-factor authentication enabled will most likely mitigate against casual attackers trying to reuse the same password on as many other online accounts as possible.

Generally, there are three forms of two-factor authentication that online services provide:

- Software token: this is the most common form, and consists in asking the user to enter in the login form a token (usually composed of six digits, sometimes it includes letters) that is sent to them either via SMS or through a dedicated app the user configured at the time of registration.

- Software push notification: the user receives a notification on the phone through an app that was installed at the time of registration. This app alerts the user that a login attempt is being made and the user can approve it or block it.

- Hardware security keys: this is a more recent form of two-factor authentication that requires the user to physically insert a special USB key into the computer in order to log into the given website.

While two-factor push notifications often provide some additional information that might be useful to raise your suspicion (for example, the country of origin of the client attempting to authenticate being different from yours), most software-based methods fall short when the attacker is sophisticated enough to employ some level of automation.

As we saw with the campaigns described in this report, if a victim is tricked into providing the username and password to their account, nothing will stop the attacker from asking to provide the 6-digits two-factor token, eventually the phone number to be verified, as well as any other required information. With sufficient instrumentation and automation, the attackers can make use of the valid two-factor authentication tokens and session before they expire, successfully log in and access all the emails and contacts of the victim. In other words, when it comes to targeted phishing software-based two-factor authentication, without appropriate mitigation, could be a speed bump at best.

Don’t be mistaken, two-factor authentication is important and you should make sure you enable it everywhere you can. However, without a proper understanding of how real attackers work around these countermeasures, it is possible that people are misled into believing that, once it is enabled, they are safe to log into just about anything and feel protected. Individuals at risk, human rights defenders above all, are very often targets of phishing attacks and it is important that they are equipped with the right knowledge to make sure they aren’t improperly lowering their level of caution online.

While it is possible that in the future capable attackers could develop ways around that too, at the moment the safest two-factor authentication option available is the use of security keys.

This technology is supported for example by Google’s Advanced Protection program, by Facebook and as of recently by Twitter as well. This process might appear painful at first, but it significantly raises the difficulty for any attacker to be successful, and it isn’t quite as burdensome as one might think. Normally, you will be required to use a security key only when you are authenticating for the first time from a new device.

That said, security keys have downsides as well. Firstly, they are still at a very early stage of adoption: only few services support them and most email clients (such as Thunderbird) are still in the process of developing an integration. Secondly, you can of course lose your security key and be locked out of your accounts. However, you could just in the same way lose the phone you use for other forms of two-factor authentication, and in both cases, you should carefully configure an option for recovery (through printed codes or a secondary key) as instructed by the particular service.

As with every technology, it is important individuals at risk are conscious of the opportunities as well as the shortcomings some of these security procedures offer, and determine (perhaps with the assistance of an expert) which configuration is best suited for their respective requirements and levels of risk.

How the Bypass for Two-Factor Authentication Works

The servers hosting the Google and Yahoo phishing sites also mistakenly exposed a number of publicly listed directories that allowed us to discover some details on the attacker’s plan. One folder located at /setup/ contained a database SQL schema likely used by the attackers to store the credentials obtained through the phishing frontend:

|

— — Database: `phishing` — — ——————————————————– — — Table structure for table `attempts` — CREATE TABLE `attempts` ( `id` int(11) AUTO_INCREMENT primary key NOT NULL, `attempts` text, `status` varchar(255) DEFAULT NULL, `timestamp` timestamp NOT NULL DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP, `sid` varchar(255) DEFAULT NULL, `information` text, `seen` tinyint(1) DEFAULT NULL ) ENGINE=InnoDB DEFAULT CHARSET=latin1; — — Table structure for table `creds` — CREATE TABLE `creds` ( `id` int(11) AUTO_INCREMENT primary key NOT NULL, `credentials` text, `status` varchar(255) DEFAULT NULL, `timestamp` timestamp NOT NULL DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP, `sid` varchar(255) DEFAULT NULL, `information` text, `seen` tinyint(1) DEFAULT NULL ) ENGINE=InnoDB DEFAULT CHARSET=latin1; |

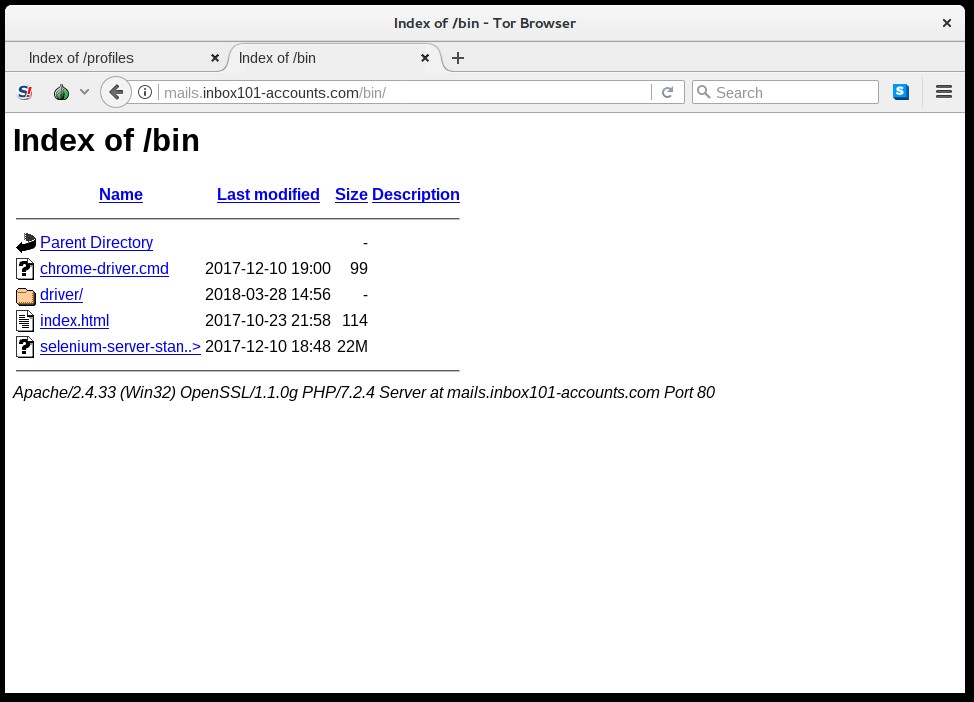

A folder located at /bin/ contained an installation of Selenium with Chrome Driver, which is a set of tools commonly used for the automation of testing of web applications. Selenium allows to script the configuration and launch of a browser (in this case Google Chrome) and make it automatically visit any website and perform certain activity (such as clicking on a button) in the page.

While the original purpose was to simplify the process of quality assurance for web developers, it also lends itself perfectly to the purpose of automating login attempts into legitimate websites and streamlining phishing attacks. Particularly, this allows attackers to easily defeat software-based two-factor authentication.

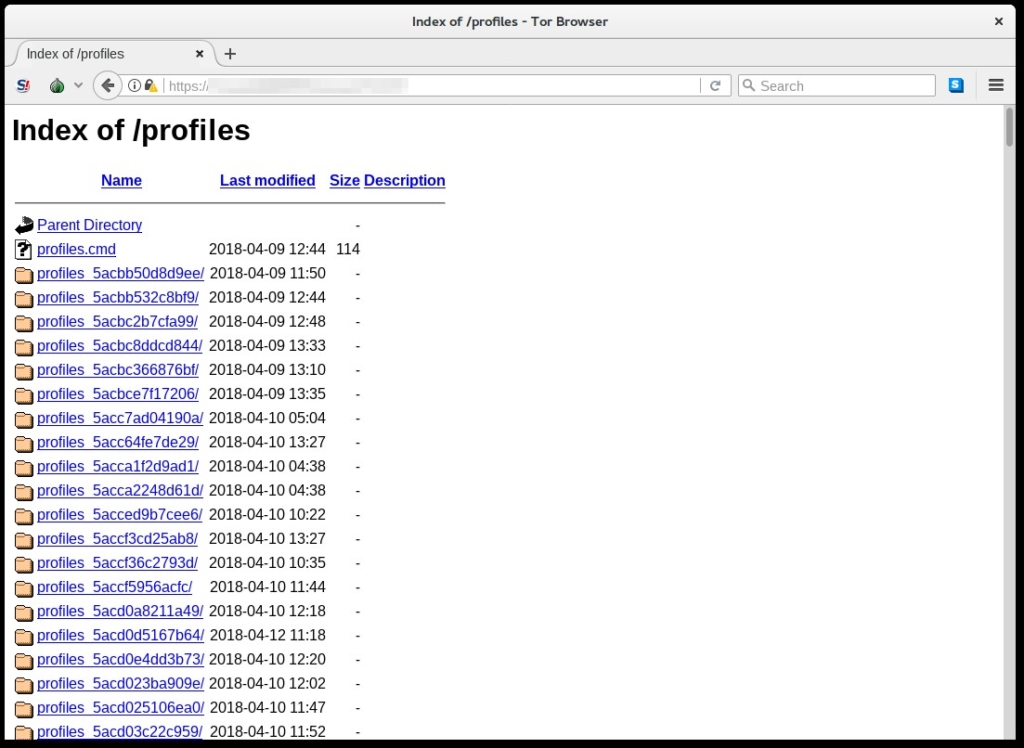

Yet another folder called /profiles/ instead contained hundreds of folders generated by each spawned instance of Google Chrome, automated through Selenium as explained.

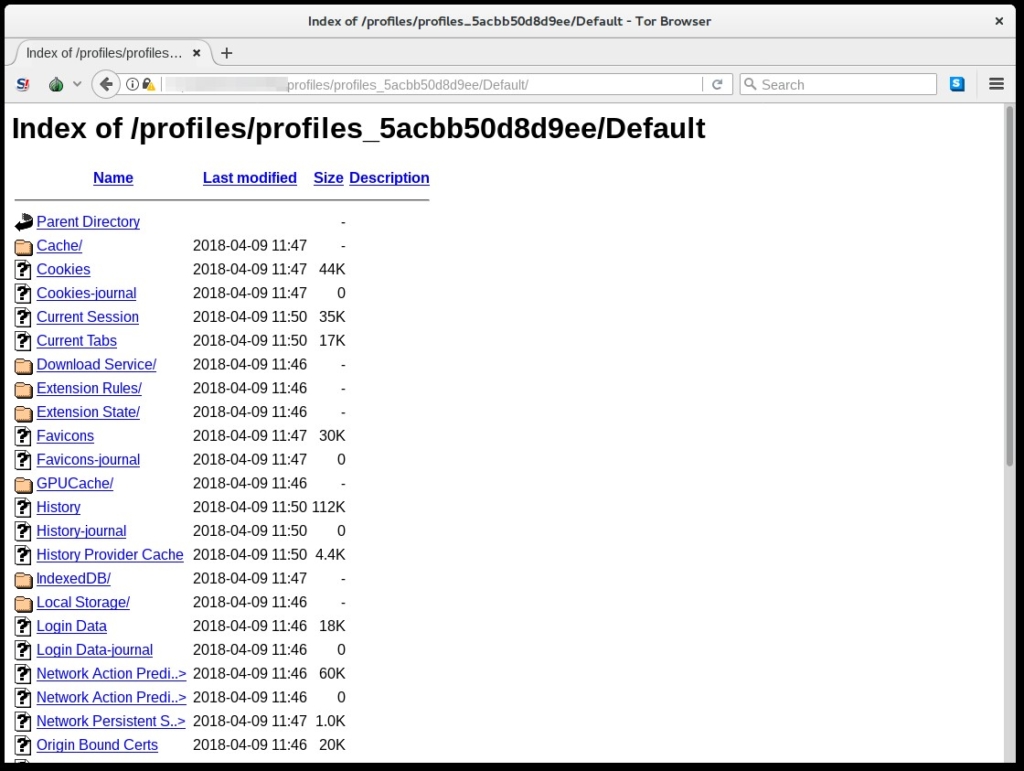

Because all the profile folders generated by the spawned Google Chrome instances operated by the attackers are exposed to the public, we can actually get a glimpse at how the accounts are compromised by inspecting the History database that is normally used by the browser to store the browsing history.

Through the many Chrome folders we could access, we identified two clear patterns of compromise.

The first pattern of compromise, and most commonly found across the data we have obtained, is exemplified by the following chronological list of URLs visited by the Chrome browser instrumented by the attackers:

- https://mail.yahoo.com/

- https://guce.yahoo.com/consent?brandType=nonEu&gcrumb=[REDACTED]&done=https%3A%2F%2Fmail.yahoo.com%2F

- https://login.yahoo.com/?done=https%3A%2F%2Fmail.yahoo.com%2F

- https://login.yahoo.com/account/challenge/push?done=https%3A%2F%2Fmail.yahoo.com%2F&authMechanism=primary&display=login&yid=[REDACTED]&sessionIndex=QQ–&acrumb=[REDACTED]

- https://login.yahoo.com/account/challenge/phone-obfuscation?done=https%3A%2F%2Fmail.yahoo.com%2F&authMechanism=primary&display=login&yid=[REDACTED]&acrumb=[REDACTED]&sessionIndex=QQ–&eid=3640

- https://login.yahoo.com/account/challenge/phone-verify?done=https%3A%2F%2Fmail.yahoo.com%2F&authMechanism=primary&display=login&yid=[REDACTED]&acrumb=[REDACTED]&sessionIndex=QQ–

- https://login.yahoo.com/account/challenge/pre-change-password?done=https%3A%2F%2Fguce.yahoo.com%2Fconsent%3Fgcrumb%3D[REDACTED]%26trapType%3Dlogin%26done%3Dhttps%253A%252F%252Fmail.yahoo.com%252F%26intl%3D%26lang%3D&authMechanism=prima$

- https://login.yahoo.com/account/security/app-passwords/list

- https://login.yahoo.com/?done=https%3A%2F%2Flogin.yahoo.com%2Faccount%2Fsecurity%2Fapp-passwords%2Flist%3F.scrumb%3D0

- https://login.yahoo.com/account/security/app-passwords/list?.scrumb=[REDACTED]

- https://login.yahoo.com/account/security/app-passwords/add?scrumb=[REDACTED]

As we can see, the attackers are automatically visiting the legitimate Yahoo login page, entering the credentials, and then following all of the required steps for eventual two-factor authentication that might have been configured by the victim. Once the full authentication process is completed, the attackers proceed to create what is commonly known as an “App Password”, which is a separate password that some services, including Yahoo, offer in order to allow third-party apps that don’t support two-factor verification to access the user’s account (for example, if the user wants to use Outlook to access the email). Because of this, App Passwords are perfect for an attacker to maintain persistent access to the victim’s account, as they will not be further required to perform any additional two-factor authentication when accessing it.

In the second pattern of compromise we identified, the attackers again seem to automate the process of authenticating into the victim’s account, but they appear to additionally attempt to perform an “account migration” in order to fundamentally clone the emails and the contacts list of from the victim’s account to a separate account under the attacker’s control:

- https://mail.yahoo.com/

- https://guce.yahoo.com/consent?brandType=nonEu&gcrumb=[REDACTED]&done=https%3A%2F%2Fmail.yahoo.com%2F

- https://login.yahoo.com/?done=https%3A%2F%2Fmail.yahoo.com%2F

- https://login.yahoo.com/account/challenge/password?done=https%3A%2F%2Fmail.yahoo.com%2F&authMechanism=primary&display=narrow&yid=[REDACTED]&sessionIndex=QQ–&acrumb=[REDACTED]

- https://login.yahoo.com/account/challenge/phone-obfuscation?done=https%3A%2F%2Fmail.yahoo.com%2F&authMechanism=primary&display=narrow&yid=[REDACTED]&acrumb=[REDACTED]&sessionIndex=QQ–&eid=3650

- https://login.yahoo.com/account/challenge/phone-verify?done=https%3A%2F%2Fmail.yahoo.com%2F&authMechanism=primary&display=narrow&yid=[REDACTED]&acrumb=[REDACTED]&sessionIndex=QQ–

- https://login.yahoo.com/account/yak-opt-in/upsell?done=https%3A%2F%2Fguce.yahoo.com%2Fconsent%3Fgcrumb%3D[REDACTED]%26trapType%3Dlogin%26done%3Dhttps%253A%252F%252Fmail.yahoo.com%252F%26intl%3D%26lang%3D&authMechanism=primary&display=n$

- https://guce.yahoo.com/consent?brandType=nonEu&gcrumb=[REDACTED]&done=https%3A%2F%2Fmail.yahoo.com%2F

- https://mail.yahoo.com/m/

- https://mg.mail.yahoo.com/neo/m/launch?

- https://mg.mail.yahoo.com/m/

- https://mg.mail.yahoo.com/m/folders/1

- https://www.gmail.com/

- https://www.gmail.com/

- https://www.google.com/gmail/

- https://mail.google.com/mail/

- https://accounts.google.com/ServiceLogin?service=mail&passive=true&rm=false&continue=https://mail.google.com/mail/&ss=1&scc=1<mpl=default<mplcache=2&emr=1&osid=1#

- https://mail.google.com/intl/en/mail/help/about.html#

- https://www.google.com/intl/en/mail/help/about.html#

- https://www.google.com/gmail/about/#

- https://accounts.google.com/AccountChooser?service=mail&continue=https://mail.google.com/mail/

- https://accounts.google.com/ServiceLogin?continue=https%3A%2F%2Fmail.google.com%2Fmail%2F&service=mail&sacu=1&rip=1

- https://accounts.google.com/signin/v2/identifier?continue=https%3A%2F%2Fmail.google.com%2Fmail%2F&service=mail&sacu=1&rip=1&flowName=GlifWebSignIn&flowEntry=ServiceLogin

- https://accounts.google.com/signin/v2/sl/pwd?continue=https%3A%2F%2Fmail.google.com%2Fmail%2F&service=mail&sacu=1&rip=1&flowName=GlifWebSignIn&flowEntry=ServiceLogin&cid=1&navigationDirection=forward

- https://accounts.google.com/CheckCookie?hl=en&checkedDomains=youtube&checkConnection=youtube%3A375%3A1&pstMsg=1&chtml=LoginDoneHtml&service=mail&continue=https%3A%2F%2Fmail.google.com%2Fmail%2F&gidl=[REDACTED]

- https://mail.google.com/accounts/SetOSID?authuser=0&continue=https%3A%2F%2Fmail.google.com%2Fmail%2F%3Fauth%3D[REDACTED]

- https://mail.google.com/mail/?auth=[REDACTED].

- https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/

- https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/#inbox

- https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/#settings/general

- https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/#settings/accounts

- https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/?ui=2&ik=[REDACTED]&jsver=OeNArYUPo4g.en.&view=mip&fs=1&tf=1&ver=OeNArYUPo4g.en.&am=[REDACTED]

- https://api.shuttlecloud.com/gmailv2/authenticate/oauth/[REDACTED]%40yahoo.com?ik=[REDACTED]&email=[REDACTED]@yahoo.com&user=0&scopes=contactsmigration,emailmigration

- https://api.login.yahoo.com/oauth2/request_auth?client_id=[REDACTED]&redirect_uri=https%3A//api.shuttlecloud.com/gmailv2/authenticate/oauth/c$

- https://api.login.yahoo.com/oauth2/authorize

- https://api.shuttlecloud.com/gmailv2/authenticate/oauth/callback?email=[REDACTED]&code=[REDACTED]

- https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/?token_id=[REDACTED]&ik=[REDACTED]&ui=2&email=[REDACTED]%40yahoo.com&view=mas

In this rather longer chronology of URLs visited by the Chrome browser instrumented by the attackers we can see that they designed the system to attempt a login into Yahoo with the stolen credentials and request the completion of a two-factor verification process, as requested by the service. Once the authentication is completed, the phishing backend will automatically connect the compromised Yahoo account to a legitimate account migration service called ShuttleCloud, which allows the attackers to automatically and immediately generate a full clone of the victim’s Yahoo account under a separate Gmail account under their control.

After such malicious account migration happened, the attackers would then be able to comfortably search and read through all the emails stolen from the victims leveraging the full-fledged functionality offered by Gmail.

Indicators

tutanota[.]org

protonemail[.]ch

accounts-mysecure[.]com

accounts-mysecures[.]com

accounts-secuirty[.]com

accounts-securtiy[.]com

accounts-servicse[.]com

accounts-settings[.]com

account-facebook[.]com

account-mysecure[.]com

account-privacy[.]com

account-privcay[.]com

account-servics[.]com

account-servicse[.]com

alert-newmail02[.]pro

applications-secure[.]com

applications-security[.]com

application-secure[.]com

authorize-myaccount[.]com

blu142-live[.]com

blu160-live[.]com

blu162-live[.]com

blu165-live[.]com

blu167-live[.]com

blu175-live[.]com

blu176-live[.]com

blu178-live[.]com

blu179-live[.]com

blu187-live[.]com

browsering-check[.]com

browsering-checked[.]com

browsers-checked[.]com

browsers-secure[.]com

browsers-secures[.]com

browser-checked[.]com

browser-secures[.]com

bul174-live[.]com

checking-browser[.]com

check-activities[.]com

check-browser[.]com

check-browsering[.]com

check-browsers[.]com

connected-myaccount[.]com

connect-myaccount[.]com

data-center17[.]website

documents-view[.]com

documents-viewer[.]com

document-viewer[.]com

go2myprofile[.]info

go2profiles[.]info

googledriveservice[.]com

gotolinks[.]top

goto-newmail01[.]pro

idmsa-login[.]com

inbox01-email[.]pro

inbox01-gomail[.]com

inbox01-mails[.]icu

inbox01-mails[.]pro

inbox02-accounts[.]pro

inbox02-mails[.]icu

inbox02-mails[.]pro

inbox03-accounts[.]pro

inbox03-mails[.]icu

inbox03-mails[.]pro

inbox04-accounts[.]pro

inbox04-mails[.]icu

inbox04-mails[.]pro

inbox05-accounts[.]pro

inbox05-mails[.]icu

inbox05-mails[.]pro

inbox06-accounts[.]pro

inbox06-mails[.]pro

inbox07-accounts[.]pro

inbox101-account[.]com

inbox101-accounts[.]com

inbox101-accounts[.]info

inbox101-accounts[.]pro

inbox101-live[.]com

inbox102-account[.]com

inbox102-live[.]com

inbox102-mail[.]pro

inbox103-account[.]com

Inbox103-mail[.]pro

inbox104-accounts[.]pro

inbox105-accounts[.]pro

inbox106-accounts[.]pro

Inbox107-accounts[.]pro

inbox108-accounts[.]pro

inbox109-accounts[.]pro

inbox169-live[.]com

inbox171-live[.]com

inbox171-live[.]pro

inbox172-live[.]com

inbox173-live[.]com

inbox174-live[.]com

inbox-live[.]com

inbox-mail01[.]pro

inbox-mail02[.]pro

inbox-myaccount[.]com

mail01-inbox[.]pro

mail02-inbox[.]com

mail02-inbox[.]pro

mail03-inbox[.]com

mail03-inbox[.]pro

mail04-inbox[.]com

mail04-inbox[.]pro

mail05-inbox[.]pro

mail06-inbox[.]pro

mail07-inbox[.]pro

mail08-inbox[.]pro

mail09-inbox[.]pro

mail10-inbox[.]pro

mail12-inbox[.]pro

mail13-inbox[.]pro

mail14-inbox[.]pro

mail15-inbox[.]pro

mail16-inbox[.]pro

mail17-inbox[.]pro

mail18-inbox[.]pro

mail19-inbox[.]pro

mail20-inbox[.]pro

mail21-inbox[.]pro

mail101-inbox[.]com

mail101-inbox[.]pro

mail103-inbox[.]com

mail103-inbox[.]pro

mail104-inbox[.]com

mail104-inbox[.]pro

mail105-inbox[.]com

mail105-inbox[.]pro

mail106-inbox[.]pro

mail107-inbox[.]pro

mail108-inbox[.]pro

mail109-inbox[.]pro

mail110-inbox[.]pro

mail201-inbox[.]pro

mail-inbox[.]pro

mailings-noreply[.]pro

myaccountes-setting[.]com

myaccountes-settings[.]com

myaccountsetup[.]live

myaccounts-login[.]com

myaccounts-profile[.]com

myaccounts-secuirty[.]com

myaccounts-secures[.]com

myaccounts-settings[.]com

myaccounts-settinq[.]com

myaccounts-settinqes[.]com

myaccounts-transfer[.]com

myaccount-inbox[.]pro

myaccount-logins[.]com

myaccount-redirects[.]com

myaccount-setting[.]com

myaccount-settinges[.]com

myaccount-settings[.]ml

myaccount-setup[.]com

myaccount-setup1[.]com

myaccount-setups[.]com

myaccount-transfer[.]com

myaccount[.]verification-approve[.]com

myaccount[.]verification-approves[.]com

myaccuont-settings[.]com

mysecures-accounts[.]com

mysecure-account[.]com

mysecure-accounts[.]com

newinbox-accounts[.]pro

newinbox01-accounts[.]pro

newinbox01-mails[.]pro

newinbox02-accounts[.]pro

newinbox03-accounts[.]pro

newinbox05-accounts[.]pro

newinbox06-accounts[.]pro

newinbox07-accounts[.]pro

newinbox08-accounts[.]pro

newinbox-account[.]info

newinbox-accounts[.]pro

noreply[.]ac

noreply-accounts[.]site

noreply-mailer[.]pro

noreply-mailers[.]com

noreply-mailers[.]pro

noreply-myaccount[.]com

privacy-myaccount[.]com

privcay-setting[.]com

profile-settings[.]com

recovery-settings[.]info

redirections-login[.]com

redirections-login[.]info

redirection-login[.]com

redirection-logins[.]com

redirects-myaccount[.]com

royalk-uae[.]com

securesmails-alerts[.]pro

secures-applications[.]com

secures-browser[.]com

secures-inbox[.]com

secures-inbox[.]info

secures-settinqes[.]com

secures-transfer[.]com

secures-transfers[.]com

secure-browsre[.]com

secure-settinqes[.]com

security-settinges[.]com

securtiy-settings[.]com

services-securtiy[.]com

settings-secuity[.]com

setting-privcay[.]com

settinqs-myaccount[.]com

settinq-myaccounts[.]com

thx-me[.]website

transfer-click[.]com

transfer-clicks[.]com

truecaller[.]services

urllink[.]xyz

verifications-approve[.]com

verification-approve[.]com

verification-approves[.]com

xn--mxamya0a[.]ccn

yahoo[.]llc

…